耶稣一下船,就有一个被污灵附着的人,从墓地里迎面而来。

那人经常住在坟墓中间,从来没有人能绑住他,甚至用锁链都不能。

曾经有很多次,人用脚镣和锁链捆绑他,锁链却被他挣断,脚镣也被他弄碎,始终没有人能制伏他。

他昼夜在坟墓里和山野间喊叫,又用石头砍自己。

(马可福音 5:2-5 新译本)

耶稣问他:『你叫什么名字?』

他回答:『我名叫「群」,因为我们众多。』

他再三央求耶稣,不要把他们从那地方赶走。

附近的山坡上有一大群猪正在吃东西;污灵求耶稣说:『打发我们到猪群那里附在猪身上吧。』

耶稣准了他们。

污灵就出来,进到猪群里去,于是那群猪闯下山崖,掉在海里淹死了,猪的数目约有两千。

放猪的人都逃跑了,到城里和各乡村去报告,大家就来看发生了什么事。

他们来到耶稣跟前,看见那被鬼附过的人,就是曾被名叫「群」的鬼附过的人,坐在那里,穿上了衣服,神志清醒,他们就害怕。

(马可福音 5:9-15 新译本)

我想起人群的疯癫历史——义和团、纳粹集中营、文化大革命、圣战萨拉菲。

论道德的谱系

On the Genealogy of Morality

前言

Preface

三 探索道德概念的起源与含义:个人旅程

3 Exploring the Origins and Implications of Moral Concepts: A Personal Journey

怀着一种我只能勉强承认的特有怀疑态度,它与道德以及迄今为止地球上被称颂为道德的一切有关——这种怀疑在我的生活中如此早地、不请自来地、不停地涌现出来,并与我的周围环境、时代、先例和传承产生了如此大的冲突,以至于我几乎有理由将其称为我的『先验』(a priori)——最终,我的好奇心和怀疑心注定会集中在我们所谓的善与恶的起源问题上。事实上,作为一个十三岁的男孩,我就已经对邪恶的起源问题感到困惑:在一个心中『半是儿童游戏,半是上帝』{Goethe, 浮士德 1. 3781行。}的年纪,我将我的第一个文学儿童游戏,我的第一篇哲学文章,献给了这个问题——至于我当时对这个问题的『解决方案』,我完全正确地将其归功于上帝,并使他成为「邪恶」的父亲。我的『先验』要我这么做吗?那种新的、不道德的,或者至少是非道德主义的『先验』:以及那种[哦,如此反康德]的、如此神秘的『绝对命令』,{伊曼努尔·康德在他的两部主要伦理学著作《道德形而上学的基础》(1785年)和《实践理性批判》(1788年)中给出了他认为的道德基本原则的多种不同表述。在《道德形而上学的基础》中,第一个『绝对命令』的表述是:『仅仅依据你同时能够希望它成为普遍法则的准则来行动』(《基础》,第一部分)。}它从中发出声音,我也在这期间越来越倾听,而且不仅仅是倾听它……幸运的是,我及时学会了将神学偏见与道德偏见分开,我不再在世界之外寻找邪恶的起源。通过一些历史和语言学的训练,加上我对所有心理问题的天生挑剔,很快将我的问题转变为另一个问题:人类在什么条件下发明了善与恶的价值判断?它们本身的价值是什么?它们迄今为止是阻碍了还是促进了人类的繁荣?它们是困境、贫困和生命退化的标志吗?或者,相反,它们揭示了生命的充盈、力量和意志,揭示了生命的勇气、信心和未来?对于这些问题,我找到了各种各样的答案,并大胆提出了自己的见解,我区分了时代、民族、个人的等级,我把我的问题专门化,并从这些答案中发展出新的问题、调查、猜想、可能性,直到我有了自己的领域,自己的土壤,一个悄然成长和开花的完整世界,仿佛是秘密花园,其存在不应被任何人察觉……哦!我们这些知识分子是多么幸福,只要我们能保持足够长时间的沉默!……

With a characteristic scepticism to which I confess only reluctantly - it relates to morality and to all that hitherto on earth has been celebrated as morality –, a scepticism which sprang up in my life so early, so unbidden, so unstoppably, and which was in such conflict with my surroundings, age, precedents and lineage that I would almost be justified in calling it my ‘a priori’, – eventually my curiosity and suspicion were bound to fix on the question of what origin our terms good and evil actually have. Indeed, as a thirteen-year-old boy, I was preoccupied with the problem of the origin of evil: at an age when one’s heart was ‘half-filled with childish games, half-filled with God’, {Goethe, Faust 1. 3781f.} I dedicated my first literary childish game, my first philosophical essay, to this problem – and as regards my ‘solution’ to the problem at that time, I quite properly gave God credit for it and made him the father of evil. Did my ‘a priori’ want this of me? That new, immoral, or at least immoralistic ‘a priori’: and the oh-so-anti-Kantian, so enigmatic ‘categorical imperative’ {Immanuel Kant gives a number of different formulations of what he takes to be the basic principle of morality in his two major works on ethics, The Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785) and the Critique of Practical Reason (1788). The first formulation of the ‘categorical imperative’ in The Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals reads: ‘Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law’ (Groundwork, section 1).} which spoke from it and to which I have, in the meantime, increasingly lent an ear, and not just an ear? … Fortunately I learnt, in time, to separate theological from moral prejudice and I no longer searched for the origin of evil beyond the world. Some training in history and philology, together with my innate fastidiousness with regard to all psychological problems, soon transformed my problem into another: under what conditions did man invent the value judgments good and evil? and what value do they themselves have? Have they up to now obstructed or promoted human flourishing? Are they a sign of distress, poverty and the degeneration of life? Or, on the contrary, do they reveal the fullness, strength and will of life, its courage, its confidence, its future? To these questions I found and ventured all kinds of answers of my own, I distinguished between epochs, peoples, grades of rank between individuals, I focused my inquiry, and out of the answers there developed new questions, investigations, conjectures, probabilities until I had my own territory, my own soil, a whole silently growing and blossoming world, secret gardens, as it were, the existence of which nobody must be allowed to suspect … Oh! how happy we are, we knowers, provided we can keep quiet for long enough! …

永恒主的话又传与我说:

人子啊,你要为推罗王举哀唱歌,对他说:

主永恒主这么说:

『你是「完美」之印章,

满有才智,十全美丽,

你曾在伊甸上帝园中,

有各样宝石做你的服饰:

就是肉红玉髓、黄玉、金钢石、

黄璧玺、水苍玉、碧玉、

蓝宝石、红玉、绿宝石;

并且你的「手鼓」和你那里的

宝石座的巧工都是金的,

是在你被创造的日子

就整备了的。

我把你安置跟一个护卫者

被膏的基路伯在一起;

你就在上帝的圣山上;

在发光如火的宝石中间往来。

从被创造的日子

你的行径就都完善,

直到在你中间发现了不义。

因为你作的生意很多,

你中间就充满了强暴的事,

以致你犯罪;

因此我抛掷你为污俗

离开上帝的山,

护卫者基路伯也将你

从发光如火的宝石中除灭掉。

你因你的美丽而心里高傲;

又为了你的光华

而败坏你的才智。

我将你摔倒于地,

使你暴露身体于君王面前,

让他们目覩为快。

因你罪孽很多,

因你作生意不公道,

你污辱了你的「圣地方」;

故此我使火从你中间发出

烧灭了你,

我就使你在所有观看的人眼前

变为地上的炉灰。

列族之民中凡认识你的

都必为你而惊骇;

你遭受了可怕的灾难,

就永远不存在了。』

(以西结书 28:11-19 吕振中)

「无灵论」是《论道德的谱系》的前提和根基。

第一章 『善与恶』、『好与坏』

First essay: ‘Good and Evil’, ‘Good and Bad’

十 贵族道德与奴隶道德的对比

10 The Dichotomy of Noble Morality and Slave Morality

奴隶道德与贵族道德的对立

奴隶道德反叛的开端发生在怨恨(ressentiment)本身变得创造性并诞生出价值的时候:那些被剥夺了行动正当反应的存在者,通过想象中的复仇来补偿自己。而所有高贵的道德则源于对自身的凯旋式的『是』的肯定,奴隶道德则原则上对一切「外在」、「他者」、「非自我」说『不』:这个『不』就是它的创造性行为。评价视角的这种逆转——这种对外在的本质性导向,而不是向自身的回溯——是怨恨的一个特征:为了形成,奴隶道德首先需要一个对立的、外在的世界,从生理学上讲,它需要外部刺激才能采取行动,——它的行动本质上是一种反应。高贵的评价方式则完全相反:它自发地行动和成长,寻找它的对立面只是为了更加感激和欢欣地对自己说『是』,——它的负面概念「低贱」、「普通」、「坏」只是其积极的基本概念之后产生的苍白对比,而这些积极概念则是充满了生命和激情:『我们是高贵的、善良的、美丽的和幸福的!』。

贵族评价方式的局限与怨恨的影响

当高贵的评价方式犯错误并违背现实时,这是在它不够熟悉的领域内发生的,在某些情况下,它错误判断了它蔑视的领域,即普通人的领域;另一方面,我们应该记住,蔑视、轻蔑和高傲的感觉带来的扭曲——假设被蔑视者的形象确实被扭曲了——远不及无力者的根深蒂固的仇恨和复仇对其对手(当然是象征性的)的攻击所造成的扭曲。事实上,蔑视中混杂了太多的轻忽、随意、自满和不耐烦,甚至还混杂着太多的个人愉快,以至于它无法将对象变成真正的讽刺和怪物。

语言中体现的贵族精神与怨恨者的心理特征

我们也不应忽视希腊贵族在用所有词语区分自己与普通人时所表现出的几乎是友好的色调;一种同情、考虑和宽容不断地渗透并掩盖它们,以至于几乎所有指普通人的词语都仍然是「不幸」、「可怜」的表达(比较 δειλός, δειλαιος, πονηρός, μοχθηρός,后两个实际上将普通人描述为奴隶劳动者和牲畜)——而且「坏」、「低贱」和「不幸」在希腊人的耳中从未停止以「不幸」为主导的音调回荡:这是古老的、更高贵的、贵族的评价方式的遗产,即使在蔑视中也不否认自己(——语言学家们会记得 οἰζυρός, ἄνολβος, τλήμων, δυςτυχεῖν, ξυμφορά 的用法)。

幸福与贵族精神的关联

「高贵」的人感觉自己是「幸福的」;他们不需要首先通过观察敌人,或者在某些情况下通过自我暗示、自我欺骗来构建自己的幸福(正如所有怨恨的人所习惯的那样);并且作为充满力量并因此必然积极的完整人类,他们知道他们必须将幸福与行动结合在一起,——行动必然被视为幸福的一部分(这是 ἐν πρᾶττειν 的词源)——这与无力者、被压迫者和充满毒性和敌对情绪的人所理解的「幸福」完全相反,对于他们来说,幸福本质上表现为麻醉剂、镇静剂、休息、平和、「安息日」、心灵的放松和四肢的舒展,简而言之,是一种被动的东西。

高贵者与怨恨者在智慧上的区别

高贵的人对自己是自信和坦率的(γενναῖος, 「贵族出生」,强调「正直」和可能的「天真」的色彩),而怨恨的人对自己既不正直也不天真,也不诚实和坦率。他的灵魂斜视;他的心灵喜欢黑暗的角落、秘密的小径和后门,一切秘密的东西都吸引他,因为那是他的世界,他的安全,他的舒适;他知道如何保持沉默、不忘记、等待、暂时谦卑和贬低自己。这样的怨恨之人必然会比任何高贵的种族更加聪明,并且会以完全不同的程度尊重聪明:即作为第一等级的生存条件,而高贵者则可以轻易地享受带有一种奢侈和精致的微妙余味的聪明:——正因为在(作为生存条件)这个方面,聪明远没有支配性的无意识本能的完全确定性重要,也远没有某种特定的缺乏聪明重要,例如大胆冲向危险或敌人,或那些由来已久的愤怒、爱、敬仰、感激和复仇的狂热突发,这些都是高贵灵魂历代以来彼此认同的标志。

怨恨对高贵者的影响与宽恕的力量

当怨恨确实在高贵者身上发生时,它被立即的反应所消耗和耗尽,因此不会毒害,另一方面,在许多情况下,它根本不会发生,而对于所有弱者和无能为力的人来说,这是不可避免的。不能长时间认真对待他的敌人、不幸,甚至是他的罪行——这是强大、圆满的天性的标志,拥有一种灵活的、塑造的、治愈的并能让人忘记的超强的力量(现代世界的一个好例子是米拉波,他对针对他的侮辱和轻视没有任何记忆并且不能饶恕人,只是因为他——忘记了)。这样的人一甩肩膀,就能抖掉许多会钻进另一个人身上的虫子;实际的『爱你的仇敌』也只在这里才有可能——假设它在地球上是可能的。{根据马太福音 5:43-44。}

贵族与敌人的关系

高贵的人对他的敌人有多么尊重!——这种尊重是一座通向爱的桥梁……因为他坚持要将他的敌人留给自己,作为一种区分的标志,实际上他会容忍的敌人只有那些没有任何可鄙之处并且值得高度尊重的人!与此相对,想象一下怨恨之人对「敌人」的设想——在这里我们看到了他的行为、他的创造:他将「邪恶的敌人」、「那恶者」构想为一个基本概念,现在他想出了一个对应物,那「良善者」——他自己!……

The beginning of the slaves’ revolt in morality occurs when ressentiment itself turns creative and gives birth to values: the ressentiment of those beings who, denied the proper response of action, compensate for it only with imaginary revenge. Whereas all noble morality grows out of a triumphant saying ‘yes’ to itself, slave morality says ‘no’ on principle to everything that is ‘outside’, ‘other’, ‘non-self’: and this ‘no’ is its creative deed. This reversal of the evaluating glance – this essential orientation to the outside instead of back onto itself – is a feature of ressentiment: in order to come about, slave morality first has to have an opposing, external world, it needs, physiologically speaking, external stimuli in order to act at all, – its action is basically a reaction. The opposite is the case with the noble method of valuation: this acts and grows spontaneously, seeking out its opposite only so that it can say ‘yes’ to itself even more thankfully and exultantly, – its negative concept ‘low’, ‘common’, ‘bad’ is only a pale contrast created after the event compared to its positive basic concept, saturated with life and passion, ‘we the noble, the good, the beautiful and the happy!’ When the noble method of valuation makes a mistake and sins against reality, this happens in relation to the sphere with which it is not sufficiently familiar, a true knowledge of which, indeed, it rigidly resists: in some circumstances, it misjudges the sphere it despises, that of the common man, the rabble; on the other hand, we should bear in mind that the distortion which results from the feeling of contempt, disdain and superciliousness, always assuming that the image of the despised person is distorted, remains far behind the distortion with which the entrenched hatred and revenge of the powerless man attacks his opponent – in effigy of course. Indeed, contempt has too much negligence, nonchalance, complacency and impatience, even too much personal cheerfulness mixed into it, for it to be in a position to transform its object into a real caricature and monster. Nor should one fail to hear the almost kindly nuances which the Greek nobility, for example, places in all words that it uses to distinguish itself from the rabble; a sort of sympathy, consideration and indulgence incessantly permeates and sugars them, with the result that nearly all words referring to the common man remain as expressions for ‘unhappy’, ‘pitiable’ (compare δειλός, δειλαιος, πονηρός, μοχθηρός, the last two actually designating the common man as slave worker and beast of burden) – and on the other hand, ‘bad’, ‘low’ and ‘unhappy’ have never ceased to reverberate in the Greek ear in a tone in which ‘unhappy’ predominates: this is a legacy of the old, nobler, aristocratic method of valuation that does not deny itself even in contempt (– philologists will remember the sense in which οἰζυρός, {‘Oi’ is an interjection expressive of pain. A person whose life gives ample occasion for the use of this interjection is ‘oizuros’.} ἄνολβος, {‘not prosperous, unfortunate’.} τλήμων, {‘tlēnai’ = to bear, endure, suffer. A person who must endure things is ‘tlemon’.} δυςτυχεῖν, {‘to have bad luck’.} ξυμφορά {‘accident, misfortune’.} are used). The ‘well-born’ felt they were ‘the happy’; they did not need first of all to construct their happiness artificially by looking at their enemies, or in some cases by talking themselves into it, lying themselves into it (as all men of ressentiment are wont to do); and also, as complete men bursting with strength and therefore necessarily active, they knew they must not separate happiness from action, - being active is by necessity counted as part of happiness (this is the etymological derivation of ἐν πρᾶττειν) {This expression (eu prattein) has something like the ambiguity of the English ‘do well’ = ‘engage in some activity successfully’ or ‘fare well’. There is no expression in common use in German with a parallel ambiguity.} – all very much the opposite of ‘happiness’ at the level of the powerless, the oppressed, and those rankled with poisonous and hostile feelings, for whom it manifests itself as essentially a narcotic, an anaesthetic, rest, peace, ‘sabbath’, relaxation of the mind and stretching of the limbs, in short as something passive. While the noble man is confident and frank with himself (γενναῖος, ‘of noble birth’, underlines the nuance ‘upright’ and probably ‘naïve’ as well), the man of ressentiment is neither upright nor naïve, nor honest and straight with himself. His soul squints; his mind loves dark corners, secret paths and back-doors, everything secretive appeals to him as being his world, his security, his comfort; he knows all about keeping quiet, not forgetting, waiting, temporarily humbling and abasing himself. A race of such men of ressentiment will inevitably end up cleverer than any noble race, and will respect cleverness to a quite different degree as well: namely, as a condition of existence of the first rank, whilst the cleverness of noble men can easily have a subtle aftertaste of luxury and refinement about it: – precisely because in this area, it is nowhere near as important as the complete certainty of function of the governing unconscious instincts, nor indeed as important as a certain lack of cleverness, such as a daring charge at danger or at the enemy, or those frenzied sudden fits of anger, love, reverence, gratitude and revenge by which noble souls down the ages have recognized one another. When ressentiment does occur in the noble man himself, it is consumed and exhausted in an immediate reaction, and therefore it does not poison, on the other hand, it does not occur at all in countless cases where it is unavoidable for all who are weak and powerless. To be unable to take his enemies, his misfortunes and even his misdeeds seriously for long – that is the sign of strong, rounded natures with a superabundance of a power which is flexible, formative, healing and can make one forget (a good example from the modern world is Mirabeau, who had no recall for the insults and slights directed at him and who could not forgive, simply because he – forgot.) A man like this shakes from him, with one shrug, many worms which would have burrowed into another man; actual ‘love of your enemies’ is also possible here and here alone - assuming it is possible at all on earth. {Gospel according to Matthew 5:43-44.} How much respect a noble man has for his enemies! – and a respect of that sort is a bridge to love … For he insists on having his enemy to himself, as a mark of distinction, indeed he will tolerate as enemies none other than such as have nothing to be despised and a great deal to be honoured! Against this, imagine ‘the enemy’ as conceived of by the man of ressentiment – and here we have his deed, his creation: he has conceived of the ‘evil enemy’, ‘the evil one’ as a basic idea to which he now thinks up a copy and counterpart, the ‘good one’ – himself! …

尼采,在第一章中,以「无灵论」的视角,阐述了「宗教」和「道德」的起源:奴隶们在「怨恨」中构想出「邪恶的魔鬼」;在「新式的爱」中构想出「良善的神」。

亚当给他妻子起名叫夏娃,因为她是众生之母。

耶和华神为亚当和他妻子用皮子作衣服给他们穿。

(创世记 3:20-21 恢复本)

耶和华说,我的意念并非你们的意念,你们的道路并非我的道路。

天怎样高过地,照样我的道路高过你们的道路,我的意念高过你们的意念。

(以赛亚书 55:8-9 恢复本)

因为除了在人里面人的灵,在人中间有谁知道人的事?照样,除了神的灵,也没有人知道神的事。

(哥林多前书 2:11 恢复本)

「堕落之前的亚当」比「堕落之后的人类」更加了解「良善的神」吗?

「良善的神」拯救了「堕落之后的亚当」吗?

「得救之后的亚当」比「堕落之前的亚当」更加了解「良善的神」吗?

「软弱无力的奴隶们」是怎么了解「良善的神」的?

弟兄们,你们看你们蒙召的,按着肉体有智慧的不多,有能力的不多,出身尊高的也不多;

神却拣选了世上愚拙的,叫那有智慧的羞愧;神又拣选了世上软弱的,叫那强壮的羞愧;

神也拣选了世上出身卑下的,以及被人藐视的,就是那些无有的,为要废掉那些有的,

使一切属肉体的人,在神面前都不能夸口。

但你们得在基督耶稣里,是出于神,这基督成了从神给我们的智慧:公义、圣别和救赎,

为使,如经上所记:『夸口的当在主里夸口。』

(哥林多前书 1:26-31 恢复本)

他们藉着信,就战胜了敌国,伸张了正义,得到了应许,堵住了狮子的口,

消灭了烈火的威力,逃脱了刀剑的锋刃,软弱变成刚强,在战争中显出大能,把外国的军队击退。

(希伯来书 11:33-34 新译本)

雅各啊!你为什么这样说;

以色列啊!你为什么埋怨说:

『我的道路向耶和华隐藏,

我的案件被我的 神忽略了』?

你不知道吗?你没有听过吗?

永在的 神、耶和华、地极的创造主

既不疲乏,也不困倦;

他的知识无法测度。

疲乏的,他赐气力,

无力的,他加力量。

就是年轻人也会疲乏困倦,

强壮的人也会全然跌倒。

但那些仰望耶和华的人,

必重新得力;

他们必像鹰一样展翅上腾;

他们奔跑,也不困倦,

他们行走,也不疲乏。

(以赛亚书 40:27-31 新译本)

「神性」里有「刚强」「谦卑」。

「魔性」里有「高傲」;「兽性」里有「软弱」。

尼采所谓的『贵族性』是一种「神性」和「魔性」的混合;

尼采所谓的『奴隶性』是一种「兽性」和「神性」的混合。

过了许久,埃及王死了。以色列人因受奴役,就叹息哀号,他们的哀声上达于神。

(出埃及记 2:23 恢复本)

恶人在骄横中,把穷苦人追得火急;愿他们陷入自己所设的计谋里!

(诗篇 10:2 恢复本)

我又见日光之下所行的一切欺压。看哪,受欺压的流泪,无人安慰;欺压他们的有势力,也无人安慰他们。

(传道书 4:1 恢复本)

耶和华必控诉民中的长老和首领,说,吃尽葡萄园果子的,就是你们;从贫穷人所夺的,都在你们家中。

(以赛亚书 3:14 恢复本)

那凭不义盖房,凭不公造楼,白白用他邻舍作工却不给工价的,有祸了。

(耶利米书 22:13 恢复本)

以色列众支派都到希伯仑来见大卫,说:『看哪!我们都是你的骨肉至亲。从前扫罗作我们的王的时候,领导以色列人行动的是你。耶和华也曾对你说:「你要牧养我的子民以色列,要作以色列的领袖。」』以色列的众长老都到希伯仑来见王。大卫王在希伯仑耶和华面前与他们立约,他们就膏立大卫作以色列的王。大卫登基的时候是三十岁,在位共四十年。他在希伯仑作犹大的王七年零六个月;在耶路撒冷作全以色列和犹大的王三十三年。

(撒母耳记下 5:1-5 新译本)

你要提醒他们服从执政的和掌权的,听从他们,随时准备作各种善工。不可毁谤人,要与人无争,谦恭有礼,向众人表现充分温柔的心。我们从前也是无知、不顺服、受了迷惑、被各种私欲和逸乐所奴役,生活在恶毒和嫉妒之中,是可憎可恶的,并且互相仇视。

然而,到了 神我们的救主显明他的恩慈和怜爱的时候,他就救了我们,并不是由于我们所行的义,而是照着他的怜悯,藉着重生的洗和圣灵的更新。圣灵就是 神藉着我们的救主耶稣基督丰丰富富浇灌在我们身上的,使我们既然因着他的恩典得称为义,就可以凭着永生的盼望成为后嗣。

这话是可信的,我愿你确实地强调这些事,使信 神的人常常留心作善工;这些都是美事,并且是对人有益的。

(提多书 3:1-8 新译本)

政府的权柄,人人都应当服从。因为没有一样权柄不是从 神来的;掌权的都是 神设立的。所以抗拒掌权的,就是反对 神所设立的;反对的人必自招刑罚。执政的不是要使行善的惧怕,而是要使作恶的惧怕。你想不怕掌权的吗?只要行善,就会得到称赞;因为他是 神的仆役,是对你有益的。但如果你作恶,就应当惧怕;因为他佩剑,不是没有作用的。他是 神的仆役,是向作恶的人施行刑罚的。所以你们必须服从,不但是因为刑罚,也是因为良心的缘故。因此,你们也当纳税,因为他们是 神的差役,专责处理这事的。你们要向各人清还所欠的;应当纳税的,就要给他纳税;应当进贡的,就给他进贡;应当敬畏的,就敬畏他;应当尊敬的,就尊敬他。

(罗马书 13:1-7 新译本)

弟兄们,我劝你们要提防那些离间你们、绊倒你们、使你们违反你们所学的教义的人。你们也要避开他们,因为这样的人不服事我们的主基督,只服事自己的肚腹,用花言巧语欺骗老实人的心。你们的顺服已经名闻各处,所以我为你们高兴。我愿你们在善事上有智慧,在恶事上毫不沾染。赐平安的 神快要把撒但践踏在你们脚下。愿我们主耶稣的恩惠与你们同在。

(罗马书 16:17-20 新译本)

你们因着自己的过犯和罪恶,原是死的。那时你们在过犯和罪恶中行事为人,随着时代的潮流,也服从空中掌权的首领,就是现今在悖逆的人身上运行的灵。

(以弗所书 2:1-2 新译本)

我儿提摩太啊!我照着从前关于你的预言,把这命令交托你,为的是要叫你藉着这些预言打那美好的仗。常常存着信心和无愧的良心。有些人丢弃良心,就在信仰上失落了。他们当中有许米乃和亚历山大,我已经把他们交给撒但,使他们受管教不再亵渎。

(提摩太前书 1:18-20 新译本)

因此,我劝你最重要的是要为万人、君王和一切有权位的恳求、祷告、代求和感恩,好让我们可以敬虔庄重地过平静安稳的日子。在我们的救主 神看来,这是美好的,可蒙悦纳的。他愿意万人得救,并且充分认识真理。因为 神只有一位,在 神和人中间也只有一位中保,就是降世为人的基督耶稣。他舍了自己作万人的赎价,到了适当的时候,这事就证实了。为了这事,我也被派作传道的和使徒(我说的是真话,不是谎言),在信仰和真理上作外族人的教师。

(提摩太前书 2:1-7 新译本)

若遇见你仇敌的牛或驴失迷了路,总要牵回来交给他。

若看见恨你之人的驴压卧在重驮之下,不可离他不顾,务要和他一同抬开重驮。

(出埃及记 23:4-5 恢复本)

以色列王见了他们,就问以利沙说,我父啊,我可以击杀他们么?我可以击杀他们么?

以利沙说,不可击杀他们。你用刀用弓掳来的,你岂会击杀他们么?当在他们面前设摆饮食,使他们吃喝,然后回到他们的主人那里。

王就为他们预备了盛大的筵席;他们吃喝完了,王打发他们离去,他们就回到自己主人那里。从此,亚兰人不再结队侵犯以色列地了。

(列王纪下 6:21-23 恢复本)

你的仇敌若饿了,就给他饭吃;若渴了,就给他水喝;

因为你这样行,就是把炭火堆在他的头上;耶和华也必赏报你。

(箴言 25:21-22 恢复本)

耶稣被接上升的日子将要到了,就硬着头皮、面向耶路撒冷走去,又差遣使者在他前面。他们就去,进了撒玛利亚的一个村庄、要为他豫备。那里的人却不接待他,因为他面向着耶路撒冷走去。他的门徒雅各、约翰看见了,就说:『主啊,你愿意我们吩咐火从天上降下来,烧灭他们么?』耶稣转过身来责备他们。就往别的村庄去了。

(路加福音 9:51-55 吕振中)

那些较为高贵的作者们,在《圣经》中,写下了低贱者们之间的爱与恨。并且,那些作者们写到:『要爱你的邻舍如同你自己』。{马可福音 12:31 吕振中}

你们听见有话说,『当爱你的邻舍,恨你的仇敌。』

但是我告诉你们,要爱你们的仇敌,为那逼迫你们的祷告,

你们就可以作你们诸天之上父的儿子;因为祂叫祂的日头上升,照恶人,也照好人;降雨给义人,也给不义的人。

(马太福音 5:43-45 恢复本)

你们站着祷告的时候,若向什么人怀怨,要赦免他,好叫你们在诸天之上的父,也赦免你们的过犯。

(你们若不赦免人,你们在诸天之上的父,也不赦免你们的过犯。)

(马可福音 11:25-26 恢复本)

十七 哲学、语言学、生理学与医学的联合探讨的必要性

17 The Need for an Interdisciplinary Approach to the History and Evaluation of Moral Concepts

备注。我借此论文的机会,公开正式表达我之前仅在与学者的私人对话中提到的一个愿望:那就是,某个哲学系能够通过一系列学术论文竞赛,推动对道德史的研究——也许这本书能在这一方向上起到有力的推动作用。关于这一可能性,我提出以下问题以供思考:它值得语言学家和历史学家,以及职业哲学家的关注:

『语言学,尤其是词源学的研究,对道德概念演变的历史提供了哪些指引?』

——另一方面,争取生理学家和医生对这些问题(关于以前所有价值判断本身的价值)的支持同样至关重要。我们可以把这一任务交给职业哲学家来充当倡导者和调解者,因为他们完全成功地将哲学与生理学和医学之间原本如此保留和猜疑的关系转变为最热诚、最富有成效的交流。事实上,历史上或民族学研究中已知的每一个价值体系,每一个『你应当』首先都需要生理学的解释和阐明,而不是心理学的解释;所有这些都需要医学的批判性研究。这个问题需要从不同角度提出:『这种或那种价值体系和「道德」值什么?』尤其是『为了什么的价值?』这一问题不应被过于粗略地看待。比如,某些东西显然对于某一族群最长可能的延续(或对适应特定气候的能力的提高,或维持最大数量)具有价值,但若是为了发展出更强种类的话,价值就截然不同了。多数人的利益和少数人的利益是相互冲突的道德立场;我们将前者本身视为更高价值的观点留给那些天真的英国生物学家们……全部科学从现在起都必须为未来哲学家的工作铺平道路:这项工作被理解为哲学家必须解决价值问题并决定价值等级顺序。——

Note. I take the opportunity presented to me by this essay, of publicly and formally expressing a wish that I have only expressed in occasional conversations with scholars up till now: that is, that some Faculty of Philosophy should do the great service of promoting the study of the history of morality by means of a series of academic prize essays: – perhaps this book might serve to give a powerful impetus in such a direction. With regard to such a possibility, I raise the following question for consideration: it merits the attention of philologists and historians as well as those who are actually philosophers by profession:

‘*What signposts does linguistics, especially the study of etymology, give to the history of the evolution of moral concepts?*’

– On the other hand, it is just as essential to win the support of physiologists and doctors for these problems (on the value of all previous valuations): we can leave it to the professional philosophers to act as advocates and mediators in this, once they have completely succeeded in transforming the originally so reserved and suspicious relationship between philosophy, physiology and medicine into the most cordial and fruitful exchange. Indeed, every table of values, every ‘thou shalt’ known to history or the study of ethnology, needs first and foremost a physiological elucidation and interpretation, rather than a psychological one; and all of them await critical study from medical science. The question: what is this or that table of values and ‘morals’ worth? needs to be asked from different angles; in particular, the question ‘value for what?’ cannot be examined too finely. Something, for example, which obviously had value with regard to the longest possible life-span of a race (or to the improvement of its abilities to adapt to a particular climate, or to maintaining the greatest number) would not have anything like the same value if it was a question of developing a stronger type. The good of the majority and the good of the minority are conflicting moral standpoints: we leave it to the naïvety of English biologists to view the first as higher in value as such … All sciences must, from now on, prepare the way for the future work of the philosopher: this work being understood to mean that the philosopher has to solve the problem of values and that he has to decide on the rank order of values. –

如何仿造人脑的良心机能和决策机能?

人脑的良心机能、决策机能与人脑海马体有什么关系?

ChatGPT:

- 良心机能

- 定义: 良心机能是指个人对道德、伦理的内在感知和判断能力。它与道德决策、善恶判断以及社会规范的遵循密切相关。

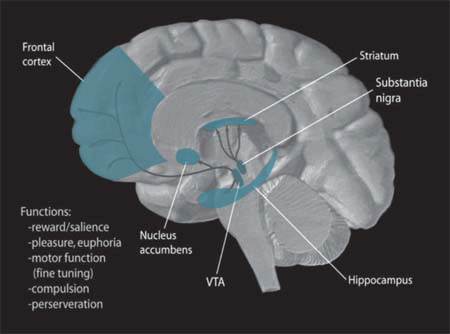

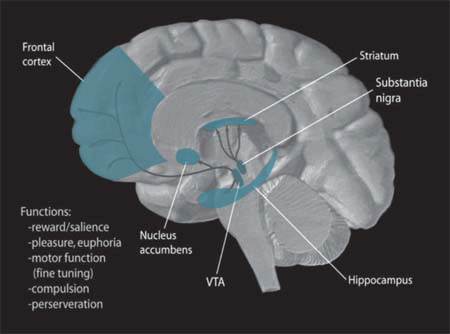

- 相关脑区: 良心机能主要涉及前额叶皮层(尤其是内侧前额叶皮层)和前扣带回皮层,这些区域与道德判断、情绪调节、自我反省等功能相关。

- 海马体的作用: 虽然海马体并不是良心机能的直接参与者,但它在记忆形成和情景记忆中扮演重要角色。良心的形成往往依赖于个体过去的经历和记忆,因此海马体间接影响了良心机能的运作。

- 决策机能

- 定义: 决策机能是指个体在面对选择时,分析、评估并最终做出决定的能力。它涉及复杂的认知过程,包括信息整合、风险评估和未来后果的预测。

- 相关脑区: 决策机能主要由前额叶皮层(尤其是背外侧前额叶皮层)负责,这一区域在理性思考、规划和冲动控制方面起重要作用。此外,伏隔核与多巴胺系统也参与了奖赏和动机相关的决策过程。

- 海马体的作用: 海马体在决策过程中通过对情景记忆和情感经验的回忆,帮助个体预测不同选择可能带来的结果。这些记忆和经验能够影响个体在决策过程中的判断,从而影响最终的决策。

- 海马体

- 定义: 海马体是大脑中负责记忆形成、学习和空间导航的重要结构。它在将短期记忆转化为长期记忆,以及情景记忆的形成中起关键作用。

- 功能: 海马体通过储存和检索记忆,帮助个体在决策和道德判断时调用过往经验,进而影响良心和决策的运作。

- 良心机能、决策机能与海马体的关系

- 相互作用: 海马体存储和处理的情景记忆和情感体验为良心和决策机能提供了重要的背景信息。通过调用这些记忆,个体可以更好地进行道德判断和复杂决策。例如,在道德困境中,海马体的记忆回调功能可以使个体联想到类似情境下的经验,从而影响良心的判断和最终的决策。

- 交叉影响: 良心机能和决策机能之间有时是紧密相连的。良心可能影响决策,特别是在涉及道德和伦理的决策中,而决策过程中的认知评估也可能会引导良心的判断。而海马体通过对相关记忆的调用,成为这两者之间重要的桥梁。

腹侧被盖区(VTA)(tegmentum 是拉丁语,意为覆盖),也被称为蔡氏腹侧被盖区,或简称为腹侧被盖,是一群位于中脑底部靠近中线的神经元群。

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) (tegmentum is Latin for covering), also known as the ventral tegmental area of Tsai, or simply ventral tegmentum, is a group of neurons located close to the midline on the floor of the midbrain.

腹侧被盖区和海马体在解剖结构和功能上有什么联系?

ChatGPT:

腹侧被盖区 (VTA) 和海马体在解剖结构和功能上有重要的联系,主要通过它们在神经回路中的相互作用来调控情绪、记忆和奖赏行为。

解剖结构上的联系

多巴胺神经元投射:VTA 是大脑中多巴胺神经元的主要来源之一。这些神经元从 VTA 投射到多个大脑区域,包括海马体。特别是,VTA 的多巴胺神经元通过中脑边缘通路向海马体的前海马皮层 (ventral hippocampus) 投射。

反馈回路:海马体也通过神经回路与 VTA 互相联系。海马体可以通过中介区域(如伏隔核和前额叶皮层)影响 VTA 的活动。这种反馈回路对于调节情绪、记忆以及与奖赏相关的行为非常重要。

功能上的联系

情绪调节:VTA 的多巴胺投射与海马体的相互作用对于情绪的调控至关重要。VTA 通过释放多巴胺影响海马体的活动,从而影响与情绪相关的记忆形成和调节。

奖赏和动机:VTA 是大脑奖赏系统的核心部分,负责处理奖励信号和动机。海马体在这一过程中起到支持作用,帮助整合与奖励相关的记忆和情境信息,从而增强对奖励的预期和动机行为。

记忆的调节:多巴胺在海马体中的作用对于长期记忆的形成尤其重要。VTA 的多巴胺释放可以增强海马体中的突触可塑性,从而有助于巩固新记忆,特别是那些与情绪和奖励相关的记忆。

总体而言,VTA 和海马体之间的联系对于理解大脑如何整合情绪、记忆和奖励信息,以产生适应性行为具有重要意义。

第二章 『负罪』、『良心谴责』及其它

Second essay: ‘Guilt’, ‘bad conscience’ and related matters

五 早期契约与补偿中的残酷角色

5 The Role of Cruelty in Early Contracts and Compensation

确实,思考这些契约关系,如前所述,会引发对创造或允许它们的原始人的各种怀疑和敌意。正是在这里,做出承诺;正是在这里,做出承诺的人必须有一个为其量身定制的记忆:正是在这里,我们可以假设存在一个充满严酷、残忍和痛苦的存储库。为了让债务人履行还款的承诺,给出承诺的庄严性和神圣性保证,并将还款的义务铭刻在他的良心中,债务人通过合同将他仍然‘拥有’和控制的东西,例如他的身体、妻子、自由或生命,甚至在某些宗教环境下,甚至他的来世、灵魂的救赎,最终甚至是坟墓中的安宁(例如在埃及,债务人的尸体即使在坟墓中也不得安宁——这种安宁对埃及人来说意义重大)。但特别是,债权人可以对债务人的身体施加各种耻辱和折磨,例如,切割债务人身体上的肉块以抵偿债务——从这个角度来看,早期的法律估价详细而恐怖地列出了个体四肢和身体部位的估价。我认为这是进步的明确证据,是一种更自由、更慷慨的计算,罗马式的公正定价,当罗马的《十二表法》规定,在这种情况下债权人切割多少都无关紧要时,‘si plus minusve secuerunt, ne fraude esto’{‘如果切割多了或少了,不应视为犯罪。’这出自《第三表》,第6节。现代版本中对此有略微不同的文本,‘se’(= sine)代替‘ne’:‘如果他们多切或少切,都应诚实进行。’}让我们明确这一补偿问题的逻辑:相当奇怪。等价的提供是,通过给予债权人一种补偿,即享有对无助者施加权力的乐趣,享受‘de faire le mal pour le plaisir de le faire’{P. Mérimée, 《给陌生人的信》(巴黎,1874),I. 8:‘为了做恶而做恶的乐趣’},这是在社会等级较低和卑微的债权人身上尤其被珍视的享受,甚至可能被视为对更高地位的前奏。通过惩罚债务人,债权人参与了主人的权利:最终他也共享了那种可以蔑视和虐待‘下等者’的高尚感觉——或者至少,当实际的惩罚权力已经转移给‘当局’时,看到债务人被蔑视和虐待。因此,补偿成为了对残酷的担保和权利。

To be sure, thinking about these contractual relationships, as can be expected from what has gone before, arouses all kinds of suspicion and hostility towards the primitive men who created them or permitted them. Precisely here, promises are made; precisely here, the person making the promise has to have a memory made for him: precisely here, we may suppose, is a repository of hard, cruel, painful things. The debtor, in order to inspire confidence that the promise of repayment will be honoured, in order to give a guarantee of the solemnity and sanctity of his promise, and in order to etch the duty and obligation of repayment into his conscience, pawns something to the creditor by means of the contract in case he does not pay, something that he still ‘possesses’ and controls, for example, his body, or his wife, or his freedom, or his life (or, in certain religious circumstances, even his after-life, the salvation of his soul, finally, even his peace in the grave: as in Egypt, where the corpse of a debtor found no peace from the creditor even in the grave – and this peace meant a lot precisely to the Egyptians). But in particular, the creditor could inflict all kinds of dishonour and torture on the body of the debtor, for example, cutting as much flesh off as seemed appropriate for the debt: – from this standpoint there were everywhere, early on, estimates which went into horrifyingly minute and fastidious detail, legally drawn up estimates for individual limbs and parts of the body. I regard it as definite progress and proof of a freer, more open-handed calculation, of a more Roman pricing of justice, when Rome’s code of the Twelve Tables decreed that it did not matter how much or how little a creditor cut off in such a circumstance, ‘si plus minusve secuerunt, ne fraude esto’. {‘If they have cut off more or less, let that not be considered a crime.’ This is from the Third Table, section 6. Modern editions read a slightly different text here with ‘se’ (= sine) for ‘ne’: ‘If they have cut off more or less, let it be honestly done.’} Let’s be quite clear about the logic of this whole matter of compensation: it is strange enough. The equivalence is provided by the fact that instead of an advantage directly making up for the wrong (so, instead of compensation in money, land or possessions of any kind), a sort of pleasure is given to the creditor as repayment and compensation, – the pleasure of having the right to exercise power over the powerless without a thought, the pleasure ‘de faire le mal pour le plaisir de le faire’, {P. Mérimée, Lettres à une inconnue (Paris, 1874), I. 8: ‘To do evil for the pleasure of doing it’.} the enjoyment of violating: an enjoyment that is prized all the higher, the lower and baser the position of the creditor in the social scale, and which can easily seem a delicious titbit to him, even a foretaste of higher rank. Through punishment of the debtor, the creditor takes part in the rights of the masters: at last he, too, shares the elevated feeling of being in a position to despise and maltreat someone as an ‘inferior’ – or at least, when the actual power of punishment, of exacting punishment, is already transferred to the ‘authorities’, of seeing the debtor despised and maltreated. So, then, compensation is made up of a warrant for and entitlement to cruelty. –

六 债务、痛苦与残酷的持续联系

6 The Persistent Link Between Debt, Suffering, and Cruelty

在这种法律义务的领域中,‘债务’、‘良心’、‘责任’、‘神圣责任’的道德概念世界就有了其孕育之地——所有伟大事物的开始都伴随着彻底而持久的血腥,就像地球上所有伟大事物的起源一样。我们是否可以补充说,这个世界从未真正摆脱过某种血腥和折磨的气息?(即使在老康德那里:道德法则也散发着残酷的气息……)。同样,正是在这里,‘债务与痛苦’的概念之间的奇异且可能无法分解的联系第一次被缝合在一起。我再次问:痛苦在多大程度上可以作为‘债务’的补偿?在于使人受苦是最高形式的快乐,以及受害方从伤害和痛苦中获得了非凡的反向快乐:使人受苦——一种真正的盛宴,正如我提到的,当它与债权人的地位和社会位置形成对比时,其价格越高。所有这些我都是在推测中说的:因为这些地下的事情难以深究,并且令人尴尬;任何笨拙地插入‘报复’概念的人只会模糊和遮蔽自己的洞察,而非澄清它(——报复本身只是把我们带回同样的问题:‘为什么使人受苦会让人感到满足?’)。在我看来,那些温顺的家宠(即现代人,即我们)的精致甚至伪善对古人庆祝快乐中残酷的程度感到反感,对他们几乎所有快乐的组成部分进行真正强力的认识:另一方面,他们对残酷的需求显得多么天真无邪,这种‘无私的恶意’(或用斯宾诺莎的话说,就是‘恶意的同情’)被假定为正常的人类属性——让良心对此给出热烈的‘是’!一个更敏锐的眼睛或许仍能发现这些最原始和基本的人类节日快乐;在《超越善恶》第七章229节中,我指着知识化和‘神化’残酷的趋势,这一趋势贯穿了整个高级文化历史(并在重要意义上构成了它)。无论如何,不久前,没有刑罚、折磨或审判火刑,举行一场皇家婚礼或大规模的民间节日是不可想象的;同样,没有人能在贵族家庭中没有可以任意发泄恶意和残酷嘲弄的生物(例如《堂吉诃德》中对公爵夫人的宫廷中的场景:今天我们阅读整部《堂吉诃德》时,嘴里有苦味,这对作者和他的 contemporaries 来说几乎是一个折磨——他们阅读时怀着清晰的良心,将其视为最有趣的书籍,使他们几乎笑得肚子疼)。看到痛苦令人愉快,使人受苦更令人愉快——这是一个艰难的命题,但古老而强大的、过于人类的命题,顺便说一句,连猿类也可能会认同:正如人们所说,设想奇异的残酷行为,它们预测并‘演示’了人类将会做的事。没有残酷,就没有盛宴:这是人类历史上最古老和最长的时期教给我们的——而惩罚也具有非常强烈的节日特性!

In this sphere of legal obligations, then, the moral conceptual world of ‘debt’, ‘conscience’, ‘duty’, ‘sacred duty’, has its breeding ground – all began with a thorough and prolonged bloodletting, like the beginning of all great things on earth. And may we not add that this world has really never quite lost a certain odour of blood and torture? (not even with old Kant: the categorical imperative smells of cruelty …). In the same way, it was here that the uncanny and perhaps inextricable link-up between the ideas of ‘debt and suffering’ was first crocheted together. I ask again: to what extent can suffering be a compensation for ‘debts’? To the degree that to make someone suffer is pleasure in its highest form, and to the degree that the injured party received an extraordinary counter-pleasure in exchange for the injury and distress caused by the injury: to make someone suffer, – a true feast, something that, as I mentioned, rose in price the more it contrasted with the rank and social position of the creditor. I say all this in speculation: because such subterranean things are difficult to fathom out, besides being embarrassing; and anyone who clumsily tries to interject the concept ‘revenge’ has merely obscured and darkened his own insight, rather than clarified it (– revenge itself just leads us back to the same problem: ‘how can it be gratifying to make someone suffer?’). It seems to me that the delicacy and even more the tartuffery of tame house-pets (meaning modern man, meaning us) revolts against a truly forceful realization of the degree to which cruelty is part of the festive joy of the ancients and, indeed, is an ingredient in nearly every pleasure they have; on the other hand, how naïve and innocent their need for cruelty appears, and how fundamental is that ‘disinterested malice’ (or, to use Spinoza’s words, the sympathia malevolens) they assume is a normal human attribute –: making it something to which conscience says a hearty ‘yes’! A more piercing eye would perhaps be able to detect, even now, plenty of these most primitive and basic festive joys of man; in Beyond Good and Evil, VII, section 229 {See below, Supplementary material, pp. 153–4.} (earlier in Daybreak, I, sections 18, 77, 113) {See below, Supplementary material, pp. 137–9, pp. 140–1, pp. 143–4.} I pointed a wary finger at the ever-growing intellectualization and ‘deification’ of cruelty, which runs though the whole history of higher culture (and indeed, constitutes it in an important sense). At all events, not so long ago it was unthinkable to hold a royal wedding or full-scale festival for the people without executions, tortures or perhaps an auto-da-fé, similarly, no noble household was without creatures on whom people could discharge their malice and cruel taunts with impunity (remember Don Quixote, for example, at the court of the Duchess: {Don Quixote, Book II, chs 31–7.} today we read the whole of Don Quixote with a bitter taste in the mouth, it is almost an ordeal, which would make us seem very strange and incomprehensible to the author and his contemporaries, – they read it with a clear conscience as the funniest of books, it made them nearly laugh themselves to death). To see suffering does you good, to make suffer, better still – that is a hard proposition, but an ancient, powerful, human-all-too-human proposition to which, by the way, even the apes might subscribe: as people say, in thinking up bizarre cruelties they anticipate and, as it were, act out a ‘demonstration’ of what man will do. No cruelty, no feast: that is what the oldest and longest period in human history teaches us – and punishment, too, has such very strong festive aspects! –

十五 斯宾诺莎对良心与惩罚效果的反思

15 Spinoza’s Reflection on Conscience and the Effects of Punishment

斯宾诺莎以一种让他显露真面目的方式(令他的批评者感到不满,他们有系统地在这一点上误解他,例如库诺·费舍尔)意识到了这一点。当时,他在某个下午翻阅着不知道是什么回忆,注意到那个著名的良心的刺痛{morsus conscientiae}对他自己究竟还有什么意义——他将善与恶归于人的想象,并愤怒地捍卫他“自由”之神的荣誉,反对那些声称上帝的一切行为都是为了达到某种善目的亵渎者(“但这将意味着上帝受命运支配,这实际上是最大的荒谬”)。对斯宾诺莎来说,世界回到了发明良心谴责之前的那种无罪状态:那么良心的刺痛变成了什么?他最终对自己说:“欢乐的对立面”,一种伴随着对过去事件的想法的悲伤,而这些事件的结果与预期相反。对于数千年来因惩罚而被逮住的做错事的人来说,他们对自己的“罪行”感受与斯宾诺莎并无不同:“这里发生了一些意外”,而不是“我不应该这样做”——他们接受惩罚就像接受疾病或不幸或死亡一样,带着那种勇敢的、顺从的宿命论,这使得俄罗斯人(例如)在处理生活方式上比我们西方人有优势。如果在那时对行为有任何批评,它来自于智慧,智慧进行批评:我们必须首先寻找惩罚的实际效果,主要在于智慧的提升,记忆的延长,意愿变得更谨慎,更少信任,从现在起更周到地处理事情,在认识到自己对于许多事情来说,始终是太弱了的某种自我评价的改进。惩罚在很大程度上可以在人与动物身上实现的是恐惧的增加,智慧的增强,欲望的掌控:惩罚以这种方式驯服了人,但并没有使他“更好”——我们更有理由断言相反的事情。(“你可以从错误中学习”这句谚语所说的,但你学到的东西也使你变坏。幸运的是,它经常使你变得愚蠢。)

Spinoza became aware of this in a way that made him show his true colours (to the annoyance of his critics, who systematically attempt to misunderstand him on this point, Kuno Fischer, {Cf. his Geschichte der neueren Philosophie (Heidelberg, 1865), 1.2.} for example), when, one afternoon, rummaging around among who knows what memories, he turned his attention to the question of what actually remained for him, himself, of that famous morsus conscientiae {‘bite of conscience’. Cf. Spinoza, Ethics III, Definitions XVI, XVII, XXVI.} – he who had relegated good and evil to man’s imagination and angrily defended the honour of his ‘free’ God against the blasphemists who asserted that God operates everything sub ratione boni {‘to attain some good’.} (‘but that would mean that God is subject to fate and would really be the greatest of all absurdities’ –). {Spinoza, Ethics Proposition II scholium 2.} For Spinoza, the world had returned to that state of innocence in which it had lain before the invention of bad conscience: what had then become of morsus conscientiae? ‘The opposite of gaudium’, {‘gladness’.} he finally said to himself, ‘– a sadness accompanied by the notion of a past event which turned out contrary to expectation.’ Eth iii, Propos. xviii Schol. i ii. For millennia, wrong-doers overtaken by punishment have felt no different than Spinoza with regard to their ‘offence’: ‘something has gone unexpectedly wrong here’, not ‘I ought not to have done that’ –, they submitted to punishment as you submit to illness or misfortune or death, with that brave, unrebellious fatalism that still gives the Russians, for example, an advantage over us Westerners in the way they handle life. If, in those days, there was any criticism of the deed, it came from intelligence, which practised criticism: we must certainly seek the actual effect of punishment primarily in the sharpening of intelligence, in a lengthening of the memory, in a will to be more cautious, less trusting, to go about things more circumspectly from now on, in the recognition that one was, once and for all, too weak for many things, in a sort of improvement of self-assessment. What can largely be achieved by punishment, in man or beast, is the increase of fear, the intensification of intelligence, the mastering of desires: punishment tames man in this way but does not make him ‘better’, – we would be more justified in asserting the opposite. (‘You can learn from your mistakes’ as the saying goes, but what you learn also makes you bad. Fortunately it often enough makes you stupid.)

十六 罪恶感的起源:从原始本能到内心挣扎

16 The Emergence of Bad Conscience: From Primal Instincts to Internal Struggle

在这一点上,我不得不给出我自己关于“良心谴责”起源的初步表达:要让这种假设被听取并不容易,它需要被思考、观察和消化。我把良心谴责视为一种严重的疾病,人类在经历最根本的变化压力下不得不屈服——这种变化使他最终发现自己被困在社会与和平的约束中。对那些半动物来说,这种变化无异于海洋生物被迫成为陆地动物或灭绝——一下子,所有本能都被贬值和“悬置”。现在他们必须用双脚行走和“支撑自己”,而此前他们是被水托起来的:一种可怕的沉重感压在他们身上。他们觉得自己在执行最简单的任务时笨拙无比,没有了熟悉的引导者来引领他们进入这个新的、未知的世界,那些无意识地将他们引向安全的调节冲动——可怜的家伙们不得不依赖思考、推论、计算和因果联系,即依赖他们那个最贫困和错误率最高的器官“意识”!我不认为地球上曾经有过如此的苦难感,如此沉重的不适感——而与此同时,旧的本能并没有突然停止它们的需求!但要满足这些需求却是困难的,甚至很少可能:它们主要不得不寻找新的,可以说是地下的满足方式。所有未向外发泄的本能都会转向内部——这就是我所谓的人类内化:随着它,人类身上进化出了后来被称为他的“灵魂”的东西。整个内心世界,最初像是在两层皮肤之间薄薄地拉伸开来,随着人的本能外在发泄的受阻,扩展和延展,获得了深度、广度和高度。那些国家组织用来保护自己免受旧的自由本能侵袭的可怕堡垒——惩罚就是这种堡垒的主要例子——导致所有那些自由、游荡、冒险的人的本能都被转向对付他自己。这种敌意、残忍、追逐、袭击、改变和毁灭的快感——所有这些都被指向了拥有这种本能的人:这就是良心谴责的起源。缺乏外部敌人和障碍,并被迫进入压抑的狭隘和习俗的统一中,人类急躁地撕裂自己,迫害自己,啃噬自己,不给自己和平并虐待自己,这个动物在笼子的栏杆上把自己打得伤痕累累,被期望“驯服”;人类,充满空虚并因思乡病撕裂,不得不从自己内在创造出冒险,一个刑讯室,一个不安全和危险的荒野——这个傻瓜,这个充满渴望和绝望的囚犯,成了良心谴责的发明者。然而,随着它,最糟糕和最狡猾的疾病被引入了,一个人类尚未恢复的疾病;人类对人类的病,对自己的病:由于与他的动物过去的强行决裂,同时跃入和坠入新的生存环境和条件,一场对所有曾经是他的力量、快乐和可怕基础的旧本能的宣战。让我们立即补充道,另一方面,动物的灵魂对自己进行反对、对自己采取立场的前景是如此新颖、深刻、前所未有、令人困惑和意义深远,以至于世界的整个性质以一种本质的方式发生了变化。确实,需要一个神圣的观众来欣赏那时开始的奇观,而这种奇观的结束尚未出现——一个太微妙、太奇妙、太矛盾和意义深远的奇观,不允许在某个可笑的星球上无意义地上演!从那时起,人类被纳入赫拉克利特的“伟大的孩子”的最意外和最激动人心的骰子游戏之中,不管你叫他宙斯还是命运——他为自己激起了兴趣、紧张、希望,几乎是确信,仿佛通过他某种东西正在被宣布,正在准备,仿佛人类不是一个终点,而只是一个路径,一个插曲,一个桥梁,一个伟大的承诺……

At this point I can no longer avoid giving a first, preliminary expression to my own theory on the origin of ‘bad conscience’: it is not easy to get a hearing for this hypothesis and it needs to be pondered, watched and slept on. I look on bad conscience as a serious illness to which man was forced to succumb by the pressure of the most fundamental of all changes which he experienced, – that change whereby he finally found himself imprisoned within the confines of society and peace. It must have been no different for these semi-animals, happily adapted to the wilderness, war, the wandering life and adventure than it was for the sea animals when they were forced to either become land animals or perish – at one go, all instincts were devalued and ‘suspended’. Now they had to walk on their feet and ‘carry themselves’, whereas they had been carried by the water up till then: a terrible heaviness bore down on them. They felt they were clumsy at performing the simplest task, they did not have their familiar guide any more for this new, unknown world, those regulating impulses that unconsciously led them to safety – the poor things were reduced to relying on thinking, inference, calculation, and the connecting of cause with effect, that is, to relying on their ‘consciousness’, that most impoverished and error-prone organ! I do not think there has ever been such a feeling of misery on earth, such a leaden discomfort, – and meanwhile, the old instincts had not suddenly ceased to make their demands! But it was difficult and seldom possible to give in to them: they mainly had to seek new and as it were underground gratifications. All instincts which are not discharged outwardly turn inwards – this is what I call the internalization of man: with it there now evolves in man what will later be called his ‘soul’. The whole inner world, originally stretched thinly as though between two layers of skin, was expanded and extended itself and gained depth, breadth and height in proportion to the degree that the external discharge of man’s instincts was obstructed. Those terrible bulwarks with which state organizations protected themselves against the old instincts of freedom – punishments are a primary instance of this kind of bulkwark – had the result that all those instincts of the wild, free, roving man were turned backwards, against man himself. Animosity, cruelty, the pleasure of pursuing, raiding, changing and destroying – all this was pitted against the person who had such instincts: that is the origin of ‘bad conscience’. Lacking external enemies and obstacles, and forced into the oppressive narrowness and conformity of custom, man impatiently ripped himself apart, persecuted himself, gnawed at himself, gave himself no peace and abused himself, this animal who battered himself raw on the bars of his cage and who is supposed to be ‘tamed’; man, full of emptiness and torn apart with homesickness for the desert, has had to create from within himself an adventure, a torture-chamber, an unsafe and hazardous wilderness – this fool, this prisoner consumed with longing and despair, became the inventor of ‘bad conscience’. With it, however, the worst and most insidious illness was introduced, one from which mankind has not yet recovered; man’s sickness of man, of himself: as the result of a forcible breach with his animal past, a simultaneous leap and fall into new situations and conditions of existence, a declaration of war against all the old instincts on which, up till then, his strength, pleasure and formidableness had been based. Let us immediately add that, on the other hand, the prospect of an animal soul turning against itself, taking a part against itself, was something so new, profound, unheard-of, puzzling, contradictory and momentous [Zukunftsvolles] on earth that the whole character of the world changed in an essential way. Indeed, a divine audience was needed to appreciate the spectacle that began then, but the end of which is not yet in sight, – a spectacle too subtle, too wonderful, too paradoxical to be allowed to be played senselessly unobserved on some ridiculous planet! Since that time, man has been included among the most unexpected and exciting throws of dice played by Heraclitus’ ‘great child’, call him Zeus or fate, {Heraclitus, Fragment 52.} – he arouses interest, tension, hope, almost certainty for himself, as though something were being announced through him, were being prepared, as though man were not an end but just a path, an episode, a bridge, a great promise …

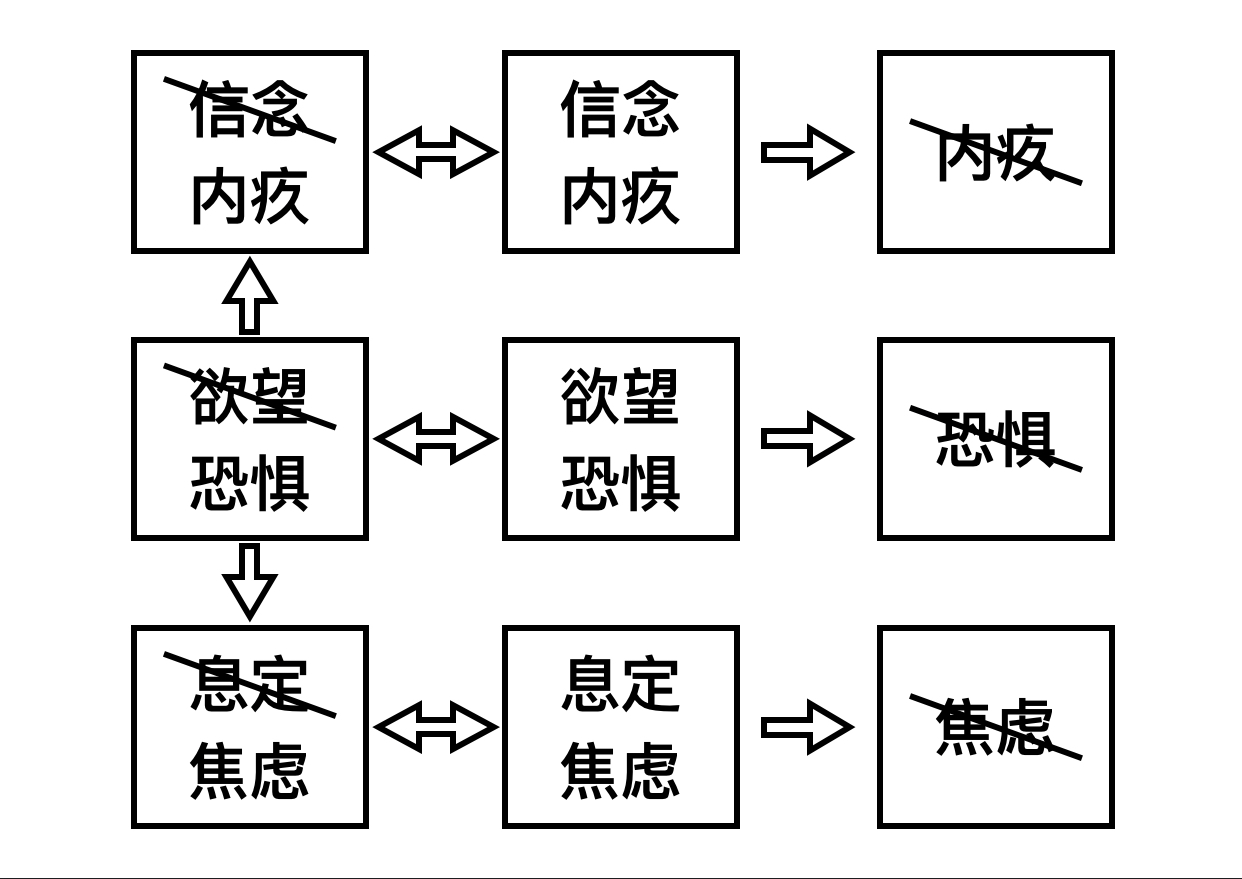

良心谴责的起源:爱的本能、勇敢的刚强向外受阻;恐惧的软弱、恨的本能向内沉积。

埃及人不过是人,并不是神;

他们的马不过是血肉,并不是灵;

永恒主一伸手,那帮助人的就绊跌,

那受帮助的也必跌倒,

二者就同归于尽。

(以赛亚书 31:3 吕振中)

人不过是人,人会困倦,人会疲乏。

人不过是人,有错的人,有罪的人。

十九 罪恶意识与神灵崇拜的起源与发展

19 The Origin and Development of Guilt Consciousness and Divine Worship

良心谴责是一种疾病,这一点无可否认,但它更像怀孕那样的疾病。让我们来研究一下这种疾病在何种条件下达到了其最可怕和崇高的顶点:我们将看到这种现象真正进入世界的情形。但我们需要极大的耐力——首先,我们必须回到更早的一个点。我已经详尽写过的民法中债务人与债权人之间的关系,在历史上以一种极其奇特的方式,再次通过解释转变成了一种关系,这种关系对我们现代人来说也许最难以理解:那就是现今一代人与他们的祖先之间的关系。在原始部落的联结中——我们讨论的是远古时代——活着的一代人总是承认他们对早先一代人,尤其是对创立部落的最早一代人负有法律责任(这不仅仅是一种感情上的联系:事实上,这种感情联系在相当长的人类历史时期内完全可以被合理否认)。普遍存在的信念是,部落的存在完全归因于祖先的牺牲和功绩——这些必须通过牺牲和功绩来偿还:人们认识到一种不断增加的负债[Schuld],因为这些祖先继续作为强大的灵魂存在,赋予部落新的优势,并将他们的一部分力量传递给部落。他们这样做难道是出于无偿的吗?但在那些粗野且“精神贫乏”的时代里,没有“无偿”这一说法。人们能拿什么来回报他们呢?牺牲(最初的牺牲是作为最粗陋意义上的食物),节日,祭坛,贡品,最重要的是,服从——因为所有的传统,作为祖先的作品,也是他们的规则和命令——:人们真的给他们足够多的东西了吗?这种怀疑依然存在并且不断增长:时不时地它要求一笔巨大的偿还,以偿还给“债权人”(例如臭名昭著的长子祭献,血祭,无论如何都是人血祭献)。沿着这条思路,随着对祖先及其力量的恐惧,对他们的债务意识不可避免地增加,这与部落自身力量的增加成正比,即部落自身变得越来越胜利、独立、受尊敬和受敬畏。并不是相反的情况!每一步走向部落的衰弱,每一次不幸的灾难,每一个退化和即将崩溃的迹象,总是减弱而不是增加对其创始人精神的恐惧,并导致对其智慧、预见力和强大存在的评价逐渐降低。如果你把这种粗暴的逻辑思考到极致:通过这种不断增长的恐惧的幻觉,最强大部落的祖先必定会膨胀到巨大的体量,并且被推向神秘和超越的幽暗中:——祖先自己最终不可避免地被升华为神。也许我们在这里看到了神的实际起源,那么,起源于恐惧!……如果有人认为‘但也出于虔诚!’的话,在人类历史上最漫长的时期,即史前时期,很难为这一观点找到合理的依据。然而,在贵族部落发展的中期,他的观点反而更加正确:——这些部落确实偿还了他们的创始人、他们的祖先(英雄、神灵)的债务,并且还带利息,用所有在他们身上已经显现出来的贵族品质来偿还。稍后,我们将再度回顾神灵是如何被尊崇和提升的过程(这完全不同于说他们被‘圣化’):但目前,让我们继续探讨这种罪恶意识发展的全过程,直到它的最终结局。

Bad conscience is a sickness, there is no point in denying it, but a sickness rather like pregnancy. Let us examine the conditions under which this sickness reached its most terrible and sublime peak: – we shall see what, with this, really entered the world. But we shall need a great deal of staying power, – and first we have to return to an earlier point. The relationship of a debtor to his creditor in civil law, about which I have written at length already, was for a second time transformed through interpretation, in a historically extremely strange and curious manner, into a relationship in which it is perhaps least comprehensible to us modern men: that is the relationship of the present generation to their forebears. Within the original tribal association – we are talking about primeval times – the living generation always acknowledged a legal obligation towards the earlier generation, and in particular towards the earliest, which founded the tribe (and this was not just a sentimental tie: this latter could, with good reason, be denied altogether for the longest period of the human race). There is a prevailing conviction that the tribe exists only because of the sacrifices and deeds of the forefathers, – and that these have to be paid back with sacrifices and deeds: people recognize an indebtedness [Schuld], which continually increases because these ancestors continue to exist as mighty spirits, giving the tribe new advantages and lending it some of their power. Do they do this for nothing, perhaps? But there is no ‘for nothing’ for those raw and ‘spiritually impoverished’ ages. What can people give them in return? Sacrifices (originally as food in the crudest sense), feasts, chapels, tributes, above all, obedience – for all traditions are, as works of the ancestors, also their rules and orders –: do people ever give them enough? This suspicion remains and grows: from time to time it exacts a payment on a grand scale, something immense as a repayment to the ‘creditor’ (the infamous sacrifice of the first-born, for example, blood, human blood in any case). Following this line of thought, the dread of the ancestor and his power, the consciousness of debts towards him, increases inevitably, in direct proportion to the increase in power of the tribe itself, that is, in proportion as the tribe itself becomes ever more victorious, independent, honoured and feared. And not the other way round! Every step towards the weakening of the tribe, all unfortunate calamities, all signs of degeneration and imminent disintegration, always lessen rather than increase the dread of the spirit of its founder, and lead to an ever lower opinion of his sagacity, providence and powerful presence. If you think this sort of crude logic through to the end: it follows that through the hallucination of the growing dread itself, the ancestors of the most powerful tribes must have grown to an immense stature and must have been pushed into the obscurity of divine mystery and transcendence: – inevitably the ancestor himself is finally transfigured into a god. Perhaps we have here the actual origin of gods, an origin, then, in fear! … And whoever should deem fit to add: ‘but in piety, too!’ would have difficulty in justifying the claim for the longest period of the human race, prehistory. All the more so, however, would he be right, for the middle period in which the noble tribes developed: – who actually did repay, with interest, their founders, their ancestors (heroes, gods) with all the attributes which, in the meantime, had become manifest in themselves, the noble attributes. Later, we shall take another look at the way gods are ennobled and exalted (which is not at all to say they were ‘hallowed’): but let us, for the present, pursue the course of this whole development of the consciousness of guilt to its conclusion.

难道「最强大的部落」会由「软弱无力的奴隶」组成吗?

二十一 罪责与宗教戒律的道德化:从良心谴责到神圣自我牺牲的转变

21 The Moralization of Guilt and Duty: From Bad Conscience to Divine Self-Sacrifice

至此,我们对‘债务/罪责’与‘责任’及宗教戒律之间关系的简要而粗略的初步概述就到这里为止了:到目前为止,我故意将这些概念的真正道德化(即它们被推回到良心中;更确切地说,是良心谴责与上帝的概念交织在一起的方式)搁置在一旁,并且在上一节的结尾,我实际上是以这些概念的道德化不存在的方式说话的,因此,好像一旦基本前提不再适用——我们对我们的‘债权人’上帝的信任,这些概念必然会消失。然而,事实却以一种可怕的方式偏离了这一点。随着‘债务/罪责’和‘责任’概念的道德化以及它们被归入良心谴责,我们实际上看到了一个试图逆转我所描述的发展方向的尝试,或者至少是阻止其发展的尝试:现在,出于悲观主义的缘故,一次性还清债务的前景被彻底关闭,现在我们的目光绝望地在一个铁定的不可能性上反弹,现在这些‘债务’和‘责任’的概念被颠倒了——但这是针对谁的呢?毫无疑问:首先是针对‘债务人’,良心谴责现在如此牢固地在他身上扎根,侵蚀他,扩展和生长,像一个水螅,变得如此广阔和深远,以至于最终随着无法偿还债务的可能性出现了无法完成赎罪的概念,无法偿还的想法(‘永罚’);最终,这也针对‘债权人’,在这里我们应该想到人类的根本原因,人类的起源,他的祖先现在背负着诅咒(‘亚当’,‘原罪’,‘意志的奴役’),或者是自然,人在其中诞生,并将罪恶的原则归咎于它(自然的妖魔化),或者是一般存在,最终被认为是本质上毫无价值的(对存在的虚无主义的背离,渴望虚无或渴望‘对立面’,成为他物,如佛教等)——直到,我们突然面对一个矛盾且恐怖的应急措施,通过这个措施,一个受难的人类寻求暂时的救赎,基督教的天才之作:没有别的,正是上帝为了人类的债务牺牲了自己,正是上帝偿还了自己,只有上帝能够赎回对人类而言已无可挽回的东西——债权人为了他的债务人牺牲了自己,出于爱(你能相信吗?——),出于对他的债务人的爱!……

So much for a brief and rough preliminary outline of the connection between the concepts ‘debt/guilt’ and ‘duty’ and religious precepts: I have so far intentionally set aside the actual moralization of these concepts (the way they are pushed back into conscience; more precisely, the way bad conscience is woven together with the concept of God), and at the conclusion of the last section I actually spoke as though this moralization did not exist, consequently, as though these concepts would necessarily come to an end once the basic premise no longer applied, the credence we lend our ‘creditor’, God. The facts diverge from this in a terrible way. With the moralization of the concepts debt/guilt and duty and their relegation to bad conscience, we have, in reality, an attempt to reverse the direction of the development I have described, or at least halt its movement: now the prospect for a once-and-for-all payment is to be foreclosed, out of pessimism, now our glance is to bounce and recoil disconsolately off an iron impossibility, now those concepts ‘debt’ and ‘duty’ are to be reversed – but against whom? It is indisputable: firstly against the ‘debtor’, in whom bad conscience now so firmly establishes itself, eating into him, broadening out and growing, like a polyp, so wide and deep that in the end, with the impossibility of paying back the debt, is conceived the impossibility of discharging the penance, the idea that it cannot be paid off (‘eternal punishment’); ultimately, however, against the ‘creditor’, and here we should think of the causa prima of man, the beginning of the human race, of his ancestor who is now burdened with a curse (‘Adam’, ‘original sin’, ‘the will in bondage’), or of nature, from whose womb man originated and to whom the principle of evil is imputed (diabolization of nature), or of existence in general, which is left standing as inherently worthless (a nihilistic turning-away from existence, the desire for nothingness or desire for the ‘antithesis’, to be other, Buddhism and such like) – until, all at once, we confront the paradoxical and horrifying expedient through which a martyred humanity has sought temporary relief, Christianity’s stroke of genius: none other than God sacrificing himself for man’s debt, none other than God paying himself back, God as the only one able to redeem man from what, to man himself, has become irredeemable – the creditor sacrificing himself for his debtor, out of love (would you credit it? –), out of love for his debtor! …

二十三 希腊神祇与基督教神观的对比:从愚蠢到神秘的罪责解释

23 A Comparison of Greek Deities and Christian Theology: From Foolishness to Mystical Guilt Explanation

关于“圣神”的降临,我们已经说得够多了——这段内容就此为止。——神的概念本身并不必然导致我们一度不得不考虑的想象力的恶化;事实上,发明神灵有比人类的自我折磨和自我摧残更高尚的用途,而欧洲在过去的几千年里恰好在这些方面表现得尤为出色——这一点可以从对希腊神灵的任何一瞥中得出结论。这些希腊神灵是高贵而自豪的人的映像,在他们身上,人类的动物性得到了神化,而不是自我撕裂或自我摧残!大多数时候,这些希腊人明确地利用他们的神灵来阻挡‘良心谴责’,以便他们能够继续享受心灵的自由:因此,这与基督教利用其上帝的方式截然相反。这些奇妙的、勇敢的孩子们在这方面做得非常彻底;甚至连荷马的宙斯这样的重要人物也让他们明白,他们这样做未免太容易了。‘奇怪!’,他在一次谈话中说道——他在谈论埃吉斯托斯的案例,一个非常糟糕的案例——

奇怪的是,凡人们竟然如此抱怨众神!他们声称只有我们带来了罪恶,但事实上,他们自己通过愚蠢的行为带来了痛苦,甚至与命运相悖!{《奥德赛》第一卷,第32到34行}

然而,我们可以立即听到并看到,即使是这位奥林匹斯的观察者和审判者也无意对此怀有怨恨或对凡人心生恶意:‘他们多么愚蠢啊’,这是他对凡人行为不端时的想法——‘愚蠢’,‘愚昧’,一点‘精神错乱’,即使是强大而勇敢的希腊人也允许自己用这些理由来解释许多恶行或灾难:——愚蠢,不是罪!你懂吗?……但即使这种精神错乱也是一个问题——‘是的,这怎么可能?像我们这样高贵出身的人,幸福、天赋优越、高贵且有德行的人,怎么会发生这样的事情?’——几个世纪以来,每当看到同伴沾染上不可理解的暴行或罪行时,贵族的希腊人都会这样问自己。‘一定是神让他迷惑了’,最后,他摇着头自言自语道……这种解决方案对希腊人来说是典型的……通过这种方式,神灵在某种程度上为人类辩护,即使他们犯了错误,神灵也作为罪恶的起因——当时他们并不承担惩罚,而是更高尚地承担了罪责……

That should be enough, once and for all, about the descent of the ‘holy God’. – That the conception of gods does not, as such, necessarily lead to that deterioration of the imagination which we had to think about for a moment, that there are nobler ways of making use of the invention of gods than man’s self-crucifixion and self-abuse, ways in which Europe excelled during the last millennia, – this can fortunately be deduced from any glance at the Greek gods, these reflections of noble and proud men in whom the animal in man felt deified, did not tear itself apart and did not rage against itself! These Greeks, for most of the time, used their gods expressly to keep ‘bad conscience’ at bay so that they could carry on enjoying their freedom of soul: therefore, the opposite of the way Christendom made use of its God. They went very far in this, these marvellous, lion-hearted children; and no less an authority than the Homeric Zeus gives them to understand that they are making it too easy for themselves. ‘Strange!’, he says on one occasion – he is talking about the case of Aegisthus, a very bad case –

Strange how much the mortals complain about the gods! We alone cause evil, they claim, but they themselves, through folly, bring about their own distress, even contrary to fate! {Odyssey I. 32–4.}

Yet we can immediately hear and see that even this Olympian observer and judge has no intention of bearing them a grudge for this and thinking ill of them: ‘How foolish they are’ is what he thinks when the mortals misbehave, – ‘foolishness’, ‘stupidity’, a little ‘mental disturbance’, this much even the Greeks of the strongest, bravest period allowed themselves as a reason for much that was bad or calamitous: – foolishness, not sin! you understand? … But even this mental disturbance was a problem – ‘Yes, how is this possible? Where can this have actually come from with minds like ours, we men of high lineage, happy, well-endowed, high-born, noble and virtuous?’ – for centuries, the noble Greek asked himself this in the face of any incomprehensible atrocity or crime with which one of his peers had sullied himself. ‘A god must have confused him’, he said to himself at last, shaking his head … This solution is typical for the Greeks … In this way, the gods served to justify man to a certain degree, even if he was in the wrong they served as causes of evil – they did not, at that time, take the punishment on themselves, but rather, as is nobler, the guilt …

尼采所谓的希腊式「治疗」就是:成为「贵族」——高傲地将自己的罪行彻底忽视并完全遗忘。

因此,所有的「奴隶」都没有「拯救」。

美国心理学家和哲学家威廉・詹姆士(William James)在《宗教心理种种》(The Varieties of Religious Experience)中将宗教体验分为几种类型,并且第一种类型宗教通常指的是『心情舒畅』或『健康心态』的宗教体验。这种类型的宗教体验往往被描述为一种积极、乐观、充满喜悦和希望的状态。詹姆士认为,这些信仰者感受到了一种与神圣或超自然力量的直接关系,使他们获得了内在的平静、幸福和安慰。

虽然我在那封信上使你们忧伤,但我现在并不后悔;其实我曾经有点后悔,因为知道那封信使你们忧伤,虽然只是暂时的。

现在我快乐,不是因为你们忧伤,而是因为你们的忧伤带来了悔改。你们依照 神的意思忧伤,凡事就不会因我们受到亏损。

因为依照 神的意思而有的忧伤,可以生出没有懊悔的悔改,以致得救;世俗的忧伤却会招致死亡。

看哪,你们依照 神的意思忧伤,在你们中间就产生了怎样的热情、申诉、愤慨、战兢、渴望、热诚、正义;你们在各方面都表明了自己在那事上是清白的。

(哥林多后书 7:8-11 新译本)

「悔改」的起源是什么?

「悔改」源于「被爱」吗?

恐惧的软弱、恨的本能向外受阻;爱的本能、勇敢的刚强向内沉积。

凡作恶的都恨光,不来接近光,免得他的恶行暴露出来。

(约翰福音 3:20 新译本)

你们每逢站着祷告的时候,若跟人有什么不对的事,总当饶恕他,好使你们在天上的父也饶恕你们的过犯。

(马可福音11:25 吕振中)

And when you stand praying, forgive, if you have anything against anyone, so that your Father who is in the heavens may also forgive you your offenses.

(Mark 11:25 Recovery Version)

狭隘的罪人不愿被人训诫也不能饶恕人。

第三章 禁欲主义理想意味着什么?

Third essay: what do ascetic ideals mean?

论道德的谱系

尼采/周弘

第一章 『善与恶』、『好与坏』

一 尼采对英国心理学家道德研究的质疑与期望

我们应当归功于这些英国心理学家的还有初探道德发生史的尝试,可惜他们并没有就此提出任何疑点。我承认,他们本身就是个疑点,他们甚至在写书之前就把一些基本观点提出来了——他们本身就很有意思!这些英国心理学家们到底想要做什么?人们发现他们总是在有意或无意地做着同一件事:就是把我们内心世界中的龌龊部分暴露出来,从中寻找积极的、先进的、于人类发展有决定作用的因素,而这是些人类智慧的尊严最不愿意看到的部位,他们就是在这些习惯势力中,在健忘中,在盲目和偶然的思想网络和思想机制中,在任何一种纯粹被动的、机械的、反射性的、微不足道的和本质上是愚蠢的部位找寻积极的因素。到底是什么东西使得这些心理学家总是朝着这一个方向努力?是否是一种隐秘的、恶毒的、低级的、连他们自己都不愿意承认的贬低人类的本能?是否是一种悲观主义的猜忌,一种对失意的、干瘪的、逐渐变得刻毒而幼稚的理想主义的怀疑?是否是对于基督教(和柏拉图)的一种渺小的、隐秘的、从未跨过意识门槛的愤忿和积怨?抑或是对于稀奇的事物、对于令人头疼的反论、对于存在本身的可疑点和荒唐处的一种贪婪的嗜好?当然,也可能是一种混合,其中含有少许卑劣、少许忧郁、少许反基督教、少许快感、少许对调味品的需求?……可是有人告诉我说,这不过是些冷血的、乏味的老青蛙,它们在人的周围爬行跳跃,好像是在它们自己的天地中:在一个泥塘中一样。我很不愿意听到这些,而且我不相信这些。假如允许人在不知情的情况下表达一个愿望的话,那么我真心地希望这些人能够是另外一副样子,希望这些灵魂的研究者们和显微观察者们能够是基本上勇敢的、高尚的、自豪的动物,能够知道如何控制他们的情感,并且训练他们自己为真理牺牲所有的欲望——为任何一种真理,哪怕是朴素的、辛辣的、丑陋的、令人不快的、非基督教的、非道德的真理,因为这种真理确实存在着。

二 『好』的真正来源

那么就向那些想支配这些道德史学家的好人们致敬吧!可惜的是,历史精神本身肯定会背弃这些道德史学家,恰恰是历史上的全体好人自己弃他们于艰难境地!他们全体都遵循已经陈旧的哲学家习俗,基本上不用历史的方法思维,这点是没有疑问的。他们撰写的道德谱系从一开始着手调查『好』的观念和判断的起源时就立刻暴露了其拙劣。他们宣称,『最初,不自私的行为受到这些行为的对象们,也就是这些行为的得益者们的赞许,并且被称之为好;后来这种赞许的起源被遗忘了,由于不自私的行为总是习惯地被当作好的来称赞,因此也就干脆被当作好的来感受——似乎它们自身就是什么好的一样。』我们立刻发现,在这第一段引言中已经包含了英国心理学家的特异性的全部典型特征。我们已经看到了『有益』、『遗忘』、『习惯』,最后还有错误,所有这些都被当成了受人尊敬的依据,迄今为止比较高贵的人们甚至引以为自豪。就像引一种人类的艺术特权为自豪一样。这种自豪应当受到羞辱,这种尊敬应当被贬值:目的达到了吗?……我现在才看清了,这种理论是在错误的地方寻找和确定『好』的概念的起源:『好』的判断不是来源于那些得益于『善行』的人!其实它是起源于那些『好人』自己,也就是说那些高贵的、有力的、上层的、高尚的人们判定他们自己和他们的行为是好的,意即他们感觉并且确定他们自己和他们的行为是上等的,用以对立于所有低下的、卑贱的、平庸的和粗俗的。从这种保持距离的狂热中他们才取得了创造价值、并且给价值命名的权利:这和功利有什么关系!功利的观点对于维持最高等级秩序的热情、突出等级的价值判断的热情表达恰恰是如此陌生和极不适宜:此刻方才出现了那种卑微的热情的对立感觉,这种热情以每一种功于心计的精明,以每一种功利的算计为前提,——而且不止一次地,不是特殊情况,而是永久的。高尚和维持距离的狂热,就是我们说过的上等的、统治艺术的那种持久的、主导的整体和基本感觉,与一种低下的艺术、一个『下人』的关系——这就是『好』和『坏』对立的起源。(主人有赐名的权利,这意味着人们可以把语言的来源理解为统治者威权的表达:他们说,『这是什么,那是什么』;他们用声音给每一物、每一事打下烙印,并且通过这种方法将其立即据为己有。)从这个起源出发——『好』这个词从一开始就根本没有必要和『不自私』的行为相关联:那是道德谱系学家们的偏见。事实上,只是在贵族的价值判断衰落的时候,『自私』和『不自私』的这种全面对立才越来越被强加于人的良知,——用我的话说,群体本能终于用言辞(而且用多数的言辞)得到了表述。此后还要经过很长的一段时间这种本能才会在群众中变成主人,使对道德价值的评定形成,并且陷入上述那种对立(这就是目前欧洲的状况:如今占据着统治地位的是成见,成见正被看作是和『道德』,『不自私』,『公平』相等同的概念,而且已经具有了一种『固定观念』和脑病特有的威力)。

三 心理分析与历史的批判

可是第二:那种关于『好』的价值判断的起源的假说除了在历史上是完全站不住脚的以外,在心理分析方面也是荒诞不经的。不自私的行为的功利被说成是该行为受到称赞的根源,而这个根源却被遗忘了——怎么可能遗忘呢?也许这种行为的功利曾在某时失效?情况恰恰相反,事实上这种功利在所有的时代都司空见惯,而且不断地得到重新强调;因此,功利不是从意识中消失了,不是被遗忘了,而是必然地越来越清晰地显现在意识中。这样一来那种反对派理论倒是更为清晰合理了(那理论并不因此而更正确——)。例如赫伯特·斯宾塞就表述了这派理论:他认为『好』的概念就其本质来说与『有益』、『实用』相通,因此在『好』和『坏』的判断中人类总结并确认的正是他们关于有益——实用和有害——不实用的那些未被遗忘和遗忘不掉的经验。根据这种理论,『好』即是那种迄今一直被证明是有益的:因此,好被看成『最高等级的有价值的』效用,被看成『自身有价值的』效用。正像我所说的,这种解释方法也是错误的,但是它本身至少是清晰合理的,而且从心理的角度上看也是站得住脚的。

四 『好』与『坏』的词源转化及其对道德研究的影响

有个问题为我指出了通向正确道路的方向,这个问题的提出本来是因为在词源学中出现了各种不同的表述『好』的词言文字:在这里我发现所有这些名称都把我们引回到同一个概念转化——基本概念的等级含义往往是『高尚』、『高贵』,由此又必然转化出含有『精神高尚』,『高贵』意思的『好』,含有『精神崇高』,『精神特权』意思的『好』;这一转化又总是伴随以另外那种转化,『普通的』、『粗俗的』、『低贱的』终于被转化成『坏』的概念,这后一种转化的最有力的例证就是德文字『坏』本身『坏』字(『Schlecht』)和『简朴』(『Schlicht』)通用——请比较『直截了当』(『Schlechtweg』,直译:『坏的方式』),『简直不堪』(『Schlechter-dings』,直译:『坏的事物』)——因此『坏』这个字起初就是这样不屑一顾地径直把简朴的,普通的人置于高尚的对立面。大约到了三十年战争时期,也就是说到了很晚的时候,上述内容才转变为现在通用的意思。——这就为我的道德谱系的研究展示了一条重要的线索,它之所以这么晚才被找到是因为在现代世界上,民主的偏见对所有追根溯源的工作施加了障碍性的影响,甚至连那个看来是最客观的自然科学和生理学领域也不例外,当然我在此只能是点出问题而已。那么这种偏见,一旦它燃起仇恨的烈焰,能给道德和历史造成什么样的特殊危害?这已由臭名昭著的布克尔事件表明了。起源于英国的现代精神的平民主义在它的故乡的土地上再次爆发,激烈得有如一座喷发的火山,伴随着迄今为止所有的火山都发出的那种令人扫兴的、噪音过大的、粗野的、不容争辩的声音。——

五 『好』与『坏』的词源与社会地位

说到我们的问题,我们完全有理由称其为一种安静的问题,它只是有选择地针对少数几个听众。同样有趣的是我们发现,那些标志着『好』的词汇和词根至今仍然含有某种不同一般的东西,使高尚者据此感到他们才是上等人。他们固然经常根据他们对权力的考虑称呼自己(称为『强有力的人』,『主人』,『领主』),或者根据这种考虑的最明显的标志称呼自己,例如称为『有钱人』,『占有者』(这个意思取自阿瑞阿语,在伊朗语和斯拉夫语中也有类似的表达),不过这些高尚者也根据一种典型的特性称呼他们自己这就是我们所要探讨的问题。例如他们称自己是『真实的』:最先这样做的是希腊贵族,其代言人是麦加诗人蒂奥哥尼斯。用来表达这个意思的词:esthlos的词根意味着一个人只要是存在的,现实的,真切的,他就是真正的人;而后,经过一个主观的转变,真正就变成了真实:在概念转化的这个阶段,真实成了贵族的口头禅,而且彻底地包含在『贵族的』词义里,以示和被蒂奥哥尼斯认之为并描述为不诚实的下等人相区别——一直到贵族没落以后,该词才最终被保留下来用于标志精神贵族,与此同时该词也变熟、变甜了。在kakos和deilois这两个词中(a-gathos的反义词:庶民)都强调了懦弱:这也许是一个提示,循此方向我们必须去寻找意思清楚得多的aga-thos 的词源。拉丁文中的坏(malus)字可以用来指深肤色,特别是黑头发的人为粗俗的人,即在雅利安人以前居住在意大利土地上的居民,他们和成为统治者的黄头发雅利安征服者种族最明显的区别就是颜色;至少克尔特语为我提供了正好类似的情况——fin(例如Fin-Qal这个名词),就是用来标志贵族的,最后被用来标志好、高贵、纯洁、本原是黄头发,以此和肤色暗、头发黑的土著居民相对照。顺便说一下,凯尔特人纯粹是黄头发人种。有人(譬如维尔科夫)错把德国人种分布图上的那些暗色头发人种聚居地段同什么凯尔特人的后裔和血缘联系在一起。其实,在这些地段居住着的是雅利安以前的德国居民(在整个欧洲情况几乎相同,从根本上说,被征服的种族最终再一次占了上风,在肤色上,在缺乏头脑上,甚至在智识本能和社会本能上,有谁赞成我们如下的观点,难道不是时髦的民主,难道不是更为时髦的无政府主义,尤其是现在所有的欧洲社会主义者对于『公社』这种最原始的社会形式的共同偏爱,难道它们的主旨不像是一种惊人的尾声,象征着征服者和主人种族的雅利安人甚至在生理上都处于劣势了吗?……)拉丁文字bonus我斗胆译为斗士;假如我可以将bonrs引溯到一个更为古老的词duonus(请比较bellum和du-ellum,以及duen-lum,在我看来,这中间好像保存了那个duonus),那么donus就可以译成与人纷争的人、挑起争端的人(duo),斗士:我们看到,在古罗马是什么使一个人形成他的『善良』。我们德国人的『好』本身难道不是标志『神圣者』,『神圣种族』的人吗?而且这难道不是和哥特人的人民(起初是贵族)的名称相一致吗?在此不宜阐述这些猜测的原因——

六 教士等级与精神优越观

政治优越观念总是引起一种精神优越观念,这一规则暂时尚未有例外(虽然有产生例外的机会),当最高等级是教士等级的时候,这一规则表现为教士们喜欢采用一种向人们提醒教士职能的称呼来作为他们的共同标志。譬如在这里我们第一次碰上了像『纯洁』和『不纯洁』这样的对立的等级观念,同样也是在这里后来产生了不再具有等级意义的『好』和『坏』的观念。但是人们应该当心,不要立刻把『纯洁』与『不纯洁』这种观念看得过重、太广,甚至看成象征性的:古人类的所有观念都应当从一开始就被理解为一堆我们几乎不能想像地粗糙的、笨拙的、浅薄的、狭窄的、直截了当的,特别是不具有代表性的东西,『纯洁的人』的最初的意思不过是洗澡的人,拒绝吃某种感染腹疾的食品的人,不和肮脏的下层妇女睡觉的人,厌恶流血的人——只此而已,岂有它哉!此外,当然,从以教士为主的贵族的全部行为可以看清楚,为什么恰恰是在这种早期阶段,价值的对立能够以一种危险的方式内向化、尖锐化。事实上,由于这种价值的对立在人与人之间最终扯开了一道鸿沟,就连精神自由的阿基利斯也难于毫不畏惧地逾越这道鸿沟。早在一开始就有某种有害的因素孕含在这种贵族气派中,孕含在这统治者的、疏远商贸的、部分是深思熟虑、部分是感情爆发的习惯中,其结果是各个时期的教士们都很快地、不可避免地感染上那种肠道疾病和神经衰弱,可是他们为自己找到了什么方法来医治他们这些疾病?——难道人们不能说这种医疗方法的最终结果已经显示比它要治愈的疾病本身还要危险百倍吗?人类自身仍然在受着那些教士们的医疗方式的后果的煎熬!让我们试想某种饮食方式(禁忌肉类),试想斋戒、节制性欲、『向沙漠』逃循(维尔·米切尔式的孤立,当然不包括由此产生的强饲法和营养过度,那里包含了医治禁欲主义理想的所有歇斯底里发作的最有效的方法);再试想,教士们的全部敌视感官的和懒惰而诡诈的形而上学,他们依据苦行僧的和使用玻璃扣而且观念固执的婆罗门的方式实行的自我催眠术,以及对其根治术——虚无的、最后的、非常可以理解的普遍厌倦(或者对上帝的厌倦——渴望和上帝结成一种神秘联盟是佛教徒所渴望的虚无,涅槃——仅此而已!)在教士们那儿一切都变得格外危险,不仅仅是医疗方式和治疗技术,而且还包括傲慢、报复、敏锐、放荡、爱情、权力追求、贞操、疾病——凭心而论,无论如何还应当加上一句:只有在这块土地上,在这块对人类和教士的生存来说基本上是危险的土地上,人才能够发展成为一种有趣的动物,只有在这里,人的精神才更高深,同时也变得凶恶了——正是这两个原因使得人迄今为止优越于其它的动物。

七 教士与贵族的价值冲突

读者已经可以猜测出,教士的价值方式可以多么轻易地脱离骑士——贵族的价值方式而向其反面发展了。在每一次这种脱离发生时都有一个契机,都是发生在教士阶层和斗士阶层相互嫉妒、无法和解的时候。骑士——贵族的价值判断的前提是一个强有力的体魄,是一种焕发的、丰富的、奔放的健康,以及维持这种体魄和健康的条件:战斗、冒险、狩猎、跳舞、比赛等等所有强壮的、自由的、愉快的行动。贵族化教士的价值方式,正像我们所看到的,具有其它的前提:战斗对他们来说是糟糕透了!正如我们所知,教士是最凶恶的敌人——为什么这么说?因为他们最无能。从无能中生长出来的仇恨既暴烈又可怕,既最富才智又最为阴毒。世界历史上最大的仇恨者总是教士,最富有才智的仇恨者也总是教士——在教士的报复智慧面前,其它所有的智慧都黯然失色。没有这种无能者提供的才智,人类历史将会过于乏味——让我们举个最重大的事例。在地球上,所有反对『高贵者』、『有力者』、『主人』、『权力拥有者』的行动都不能和犹太人在这方面的所为同日而语:犹太人,那个教士化的人民,深知只需彻底地重新评定他们的敌人和压迫者的价值,也就是说,以一种最富有才智的行动而使自己得到补偿。这正适合于教士化的人民,这个有着最深沉的教士化报复心理的人民。正是犹太人敢于坚持不懈地扭转贵族的价值观念(好=高贵=有力=美丽=幸福=上帝宠儿),而且咬紧了充满深不可测的仇恨(无能的仇恨)的牙关声称『只有苦难者才是好人,只有贫穷者、无能者、卑贱者才是好人,只有忍受折磨者、遭受贫困者、病患者、丑陋者才是唯一善良的、唯一虔诚的,只有他们才能享受天国的幸福,——相反,你们这些永久凶恶的人、残酷的人、贪婪的人、不知足的人、不信神的人,你们也将遭受永久的不幸、诅咒,并且被判入地狱!』……我们知道,是谁继承了这种犹太人对价值的重新评价。一想起这可怕的、祸及全体大众的首创,这一由犹太人提出的所有战争挑战中最根本的挑战,我就记起我在另一场合(《善恶的彼岸》第一一八页)说过的话——即犹太人开始了道德上的奴隶起义:那起义已经有了两干年的历史,我们今天对此模糊不清只是因为那起义取得了完全的成功……

八 犹太人如何通过耶稣实现价值观的终极逆转

——可是你们没有听懂?你们没有看到某种东西需要两千年的时间才能取得成功?……这没有什么奇怪的:所有长期性的发展都很难观察、很难判断。可这是个大事:从那报复的树干中,从那犹太的仇恨中,从那地球上从未有过的最深刻、最极端的、能创造理想、转变价值的仇恨中生长出某种同样无与伦比的东西,一种新的爱,各种爱中最深刻最极端的一种:——从其它哪根树干中能够长出这种爱?……但是也不要误以为这种爱是对那种报复渴望的否定,是作为犹太仇恨的对立面而萌发的!不是的!事实恰好相反!这种爱正是从那树干中长出来的,是它的树冠,是凯旋的、在最纯洁的亮度和阳光下逐渐逐渐地伸展开来的树冠。既使在光线和高度的王国里,这树冠也似乎以同样的渴求寻求着那仇恨的目的、胜利、战利品、诱惑,这种渴求使那种仇恨的根在所有的深渊中越扎越深,在所有的罪恶中越变越贪。拿撒勒斯的这位耶稣,爱的人格化福音,这位把祝福和胜利带给贫苦人、病患者、罪人的『救世主』,——他难道不正是最阴险可怕、最难以抗拒的诱惑吗?这诱惑和迂回不正是导向那些犹太的价值和理想的再造吗?难道以色列不正是通过这位『救世主』的迂回,这位以色列表面上的仇敌和解救者来达到其精心策划的报复行动的最后目标的吗?这难道不算是报复的一种真正重大的策略所使用的秘密非法的艺术吗?这不是一种有远见的、隐蔽的、缓慢的和严密策划的报复吗?以色列本身不正是这样被迫当着整个世界像唾弃死敌一样唾弃其报复的真正工具、并且让它钉在十字架上,从而使『整个世界』,即所有以色列的敌人,都不假思索地吞下这诱饵吗?难道还有人能从精神的所有诡计中再想出一种更加危险的诱饵吗?什么东西的诱惑人、陶醉人、麻痹人、使人堕落的力量能和『神圣的十字架』这个象征、『钉在十字架上的上帝』那恐怖的自相矛盾、上帝为了人类幸福而把自己钉在十字架上这种无法想像的最后的残酷行动的神秘色彩相提并论?至少可以肯定,以色列以这种情景,用其对迄今为止所有价值的报复和重新评定,不断地战胜了一切其它的理想,战胜一切更高贵的理想。——

九 胜利与败血症

——『可是您还谈论什么更高贵的理想!让我们顺应现实吧!人民获得了胜利——或者说是「奴隶」获得了胜利,或者说是「暴民」,或者说是「百姓」,随便您怎么去称呼它,反正这胜利是由于犹太人而获得的,而发起的!任何其他的人民都未曾有过这样一种世界历史使命。「主人」被打败了,平民的道德取得了胜利。这种胜利同时又可以被看成是一种败血症(它已经在各个种族中融通蔓延),我不否认,无疑地,人类中毒了。「拯救」人类于「主人」的统治的事业正获全胜。一切都明显地犹太化了,或者基督化了,或者暴民化了。(不管用什么词吧!)这种毒症在人类全身的蔓延看来是不可阻止的了,其蔓延的速度从现在起倒是可能不断地放慢,变得更细致、更微弱、更审慎——人们还有时间……如今教会还能有什么了不起的任务,甚至还有什么存在的理由?也许人们可以不需要教会?请回答吧。看上去教会是在阻止和控制而不是促进毒症的蔓延?这正可能是它的有用之处。可以肯定地说,教会简直就是粗鲁村野的东西,是和细腻的智慧,和一种本来很时髦的趣味相对立的,它难道不应当至少自我完善一点儿吗?……它如今得罪的人要比它诱惑的人多了……假如没有教会,我们之中有谁会成为自由思想家?是教会而不是它的毒素在和我们作对……撇开教会,我们还是热爱毒素的……』——这是一位『自由思想家』对我的讲话的反应——他是一个诚实的家伙,反正他明显地表现出他是一个民主主义者,他一直在倾听我讲话,而且不容我沉默,可是我在这个问题上却有充分的理由沉默。

十 高贵道德与奴隶道德

奴隶在道德上进行反抗伊始,怨恨本身变得富有创造性并且娩出价值:这种怨恨发自一些人,他们不能通过采取行动做出直接的反应,而只能以一种想像中的报复得到补偿。所有高贵的道德都产生于一种凯旋式的自我肯定,而奴隶道德则起始于对『外界』,对『他人』,对『非我』的否定:这种否定就是奴隶道德的创造性行动。这种从反方向寻求确定价值的行动——值得注意的是,这是向外界而不是向自身方向寻求价值——这就是一种怨恨:奴隶道德的形成总是先需要一个对立的外部环境,从物理学的角度讲,它需要外界刺激才能出场,这种行动从本质上说是对外界的反应。高贵的价值评定方式则相反;这些价值是自发地产生和发展的,它只是为了更心安理得、更兴高采烈地肯定自己才去寻找其对立面。它们的消极的概念如『低贱』、『平庸』、『坏』都是在与它们的积极的概念相比较后产生的模糊的对照,而它们的积极的概念则是彻底地渗透于生命和热情的基本概念:『我们是高贵者,是好人;我们是美的、是幸福的。』如果说贵族的价值方式有过失,强暴现实,那么这种情况就发生于他们不够了解的领域,他们不是去了解实情,而是矜持地进行自卫:有时他们会错误地判断一个他们所蔑视的领域,比如平民的领域,地位低下的人民的领域。另一方面,人们也要考虑到,不管怎么说,蔑视的情绪、倨傲的情绪、自负的情绪的产生,人们对蔑视情景的伪造,这都远远无法和无能者以受压抑的仇恨向他的对手(当然是虚构的)进行报复的那种虚伪相比。事实上,在这种蔑视中有过多的疏忽和轻浮,过多的不顾事实和不耐烦,夹杂着本来就过多的与生俱来的愉快心情,使这种蔑视能够把它的对象转变成真正的丑角和怪物。请注意,希腊贵族为了和地位低下的人民拉开距离,在所有有关的词句中加上几乎是仁慈的声调,怜悯、关怀、容忍这类的词一直不断地相互搅拌,并且包裹上糖衣,直至最后几乎所有和平民有关的词句就只省下了诸如『不幸』、『可怜』这类的表达(参见deilos,deilaios,poneros,mo-chtheros,最后两个词的本意认平民为工作奴隶和负重的牲畜)——而另一方面,『坏』、『低贱』、『不幸』这类词又没完没了地用一个单音,用一种『不幸』占优势的音色,轰击着希腊人的耳朵;这是古老的、更高贵的贵族价值方式的传家宝,即使在蔑视时也不会须臾背弃。『出身高贵者』的确感到他们自己是『幸福者』,他们不是先和他们的敌人比较,然后才来人为地造就他们的幸福,或者使人相信,或者骗人相信他们的幸福(所有充满仇恨的人们都惯于此道)。他们浑身是力,因此也必然充满积极性,同样,他们知道,不能把行动从幸福中分离出去,他们把积极行动看成幸福的必要组成部分。所有这些都和无能者以及受压抑者阶层的『幸福』形成鲜明的对立,他们这些人感染了有毒和仇恨的情感,这些情感很快就被消极地表现为麻醉、晕眩、安宁、自由、『安息日』、修养性情和伸展四肢等。高贵的人生活中充满自信和坦率(『血统高贵』强调『真诚』,或许还有『天真』),而怀恨的人既不真诚也不天真,甚至对自己都不诚实和直率,他的心灵是斜的,他的精神喜欢隐蔽的角落、秘密的路径和后门;任何隐晦的事都能引起他的兴趣,成为他的世界、他的保障、他的安慰,他擅长于沉默、记忆、等待,擅长于暂时地卑躬屈膝、低声下气。这种仇恨者的种族最终必然会比任何一个高贵的种族更加聪明,而且它对聪明尊崇的程度也大不相同:它把聪明当做其生存的首要条件,而高贵者只是把聪明当作奢侈和精致的一种高雅的变味品来享受:——即使在这方面,聪明比起无意识的调节本能那样一种完美的功能性保障也早已不那么重要了,甚至比起一种特定的不聪明来,比起某种更加勇敢的蛮干,哪怕蛮干会招灾树敌,比起那为所有时代的高尚灵魂都要重新认识的激怒、热爱、敬畏、感激和报复等等狂热的情感爆发来,聪明早已不再重要了。当一个高贵的人感受到怨恨的时候,这怨恨会爆发,并且消耗在一种瞬间的反应中,因此也就不会起毒化作用:此外,在许多场合下,高贵者丝毫不感到怨恨,而所有的软弱者和无能者却会毫无例外地感到怨恨。具有坚强完美的天性的人的标志是根本不会长期地把自己的敌人、不幸和失误看得很严重,因为他们有丰富的塑造力、修复力、治愈力,还有一种忘却力(现代世界上有个很好的例子,他就是米拉保,他记不住任何别人对他的侮辱和抵毁,他不能原谅别人,只是因为他把一切全忘记了。)这种人猛然一甩就抖落了许多寄生虫,而这些寄生虫却深入其他人的皮下;也只有在这种情况下地球上才可能出现所谓的『爱自己的敌人』。一个高贵者已经向他的敌人表示了多少尊重!而这种尊重本身就是通向爱的桥梁……是的,他以己度自己的敌人,以自己的高标准要求敌人!是的,除了这种丝毫不值得蔑视,而且非常值得尊敬的敌人,他不能容忍其他种的敌人!试想,一个充满仇恨的人构想出来的『敌人』将是什么样的——这正是他的行动,他的创造:他构想了『丑恶的敌人』,构想了『恶人』,并且把它作为基本概念,然后又从此出发产生了余念,设想了一个对立面,即『好人』——也就是他自己。

十一 价值的起源与文化的冲突

正好相反,精神高贵者预先自发地创造了『好』的基本概念,也就是说从自身获得了这一概念,而后才由此引伸出一种关于『坏』的概念!这种起源于高贵的『坏』和那种产生于不知魇足的仇恨的大锅中的『恶』——这看上去同样是『好』的概念的反义词的『坏』和『恶』是多么不相同啊!前者是附产品,是一种附加成分,一种补充色调,而后者却是本源、是起点,在奴隶的道德观念中是原始的创造活动。可是在这里同样被称为『好』的概念并不相同:最好还是过问一下,依照仇恨的道德究竟谁是『恶人』。最确切的答案是:这里的所谓『恶人』恰恰是另一种道德中的『好人』、高贵者、强有力者、统治者,他们只不过是被仇恨的有毒眼睛改变了颜色、改变了含义、改变了形态。在这里我们至少要否定一点:谁要是把那种『好人』只认作敌人,那么他除了邪恶的敌人就什么也不认识。同样是这种人,他们被如此严格地束缚在习俗、敬仰、礼节、感戴之中,甚至被束缚在相互监视、彼此嫉妒之中,他们在相互态度的另一方面却显示出如此善于思考,善于自我克制,如此温柔、忠诚、自豪、友好;一旦来到外界,接触到各种陌生事物,他们比脱笼的野兽好不了多少,他们摆脱了所有社会的禁锢,享受着自由,他们在野蛮状态中弥补着在和睦的团体生活中形成的长期禁锢和封闭所带来的紧张心理,他们返回到了野兽良心的无辜中,变成幸灾乐祸的猛兽,他们在进行了屠杀、纵火、强暴、殴打等一系列可憎的暴行之后也许会大摇大摆、心安理得地离去,仿佛只是完成了一场学生式的恶作剧,他们也许还相信,在很长一段时间内诗人们又有值得歌咏和颂扬的素材了。所有这些高贵种族的内心都是野兽,他们无异于非常漂亮的、伺机追求战利品和胜利的金发猛兽;隐藏着的内心时不时地会爆发出来,野兽必然要重新挣脱,必然要回到野蛮状态中去——罗马的贵族、阿拉伯的贵族、日耳曼的和日本的贵族,荷马史诗中的英雄和斯堪的纳维亚的海盗,他们都同样具有这种需要。高贵的种族不论走到哪里都留下了形成『野蛮人』的概念的痕迹,就连他们的最高等的文化中也显露出他们对于此种行为的一种意识,甚至是一种自豪(例如佩利克勒斯在那篇著名的葬礼演说辞中对他的雅典人民说:『我们的果敢打开了进入所有土地和海域的通道,在四外都不分好坏地树立起永恒的纪念碑。』)高贵种族的这种表现得如此疯狂、荒谬、突兀的『果敢』,这种不捉摸,这种甚至对他们自己的行动都难以把握(佩利克勒斯特别强调了雅典人的rathumia),他们的这种满不在乎,以及对安全、肉体、生命、舒适的蔑视,对所有破坏行为,对所有胜利的淫欲和残酷的淫欲的那种令人恐惧的兴致和发自内心的爱好——所有这一切都为他们的受害者勾画出『野蛮人』、『邪恶的敌人』的形象,或许是『哥特人』或者『汪达尔人』的形象。日耳曼人在初掌政权时激发的(现在又再次激发的)深刻和冷酷的不信任还总是那种无法消除的恐惧的尾声,许多世纪以来,欧洲怀着这种恐惧目睹了金发的日耳曼猛兽的震怒(虽然所有的古日耳曼人和我们德意志人之间几乎不存在概念上的联系,更不用说血源上的联系了)。我有一次注意到赫西奥特的困难处境,当时他正思考文化时代的序列问题,并试图用金、银、铁来标志它们。他善于巧妙地处理光辉的、但也是如此可怖、如此残暴的荷马时代遗留下来的矛盾,使用的方法无非是把一个时代一分为二,然后依序排列——首先是特洛伊和底比斯的那个英雄和半神的时代,这是贵胄们仍旧保留在记忆中的那个时代,在那个时代有他们自己的祖先;接下去是金属的时代,也就是那些被践踏者、被剥夺者、被残害者、被拖走和被贩卖者的后代所看到的那个世界:据说这是矿石的时代,坚硬、冷酷、残忍、没有情感和良心;一切都被捣毁并沾满血污。假定,现在被当作『真理』的东西果如其然,假定一切文化的意义就在于把『人』从野兽驯化成一种温顺的、有教养的动物、一种家畜,那么我们就必须毫不犹豫地把所有那些反对的和仇恨的本能,那些借以最终羞辱并打倒了贵胄及其理想的本能看作是真正的文化工具,当然无论如何不能说,那些具有这种本能的人本身同时也体现了文化。其实,相反的结论的正确性不仅是可能的,不!这在如今已是有目共睹的了!这些具有贬低欲和报复欲本能的人,这些所有欧洲的和非欧洲的奴隶的后代,特别是所有前亚利安居民的后代,他们体现的是人类的退让!这些『文化工具』是人类的耻辱,其实是一种怀疑,一种对『文比』的反驳!人们完全有理由惧怕并防犯所有高贵种族内心的金发猛兽,如果有人能够领悟到,不恐惧则永远无法摆脱失败者、贬低者、萎靡者、中毒者的嫉妒的眼光,难道他还会千百次地选择恐惧吗?这不正是我们的灾难吗?如今是什么构成了我们对『人』的反感?人使我们受苦,这是没有疑问的了,当然不是因为我们惧怕他,其实他已经没有什么值得惧怕的了。虫『人』已经登台,而且是蜂拥而至。『驯服的人』、不可药救的中庸者、令人不快的人已经知道把自己看成是精英,是历史的意义,是『上等人』。是的,他们的这种感觉并不是完全没有理由的,因为他们感到自己和大批失败者、病患者、疲惫者、萎靡之间尚有距离,在这段距离之后,当今的欧洲正在开始发臭,因此他们觉得自己至少还是比较适度的,至少还是有生活能力的,至少还是肯定生活的……

十二 从恶劣环境到虚无主义的反思

此刻,我不拟压抑我的感叹和我最后的期望。什么东西是我完全无法忍受的?是我独自一人无法结束的?是令我窒息、使我忍受煎熬的?是恶劣的空气!恶劣的空气!是某种失败的东西在接近我,是我被迫去嗅一种失败者的内脏……除此之外,人还有什么不能忍受的?苦难、贫困、恶劣天气、久病不愈、艰辛、孤寂?人基本上是能够对付其余这些困难的;人生来就是一种地下的、战斗的存在;人总是会不断地接触到光亮,不断地经历他的胜利的黄金时刻——然后就停留在那儿,好像生来就是这样的坚不可摧,这样急切准备迎接新的、更艰难、更遥远的战斗,就像一张弓,任何困难都只能使它绷得更紧。不过我时常得到恩赐——假设在善恶的彼岸当真存在着上界的恩赐者——使我能看一眼,而且也只能看一眼某种完美的、圆满的、幸福的、有力的、凯旋的、多少还能引起恐惧的东西!看一眼为人作辨护的人,看一眼人的那残存的、正在消失的机运,以便能够保持对人的信任!……因为事实是欧洲人正在变得渺小和平均,因为看到这种情况就使人厌倦……我们如今已不再能够看到任何会变得更伟大的东西。我们担心的是,人还在继续走下坡路,还在变得更仔细、更温和、更狡黠、更舒适、更平庸、更冷漠、更中国式、更基督化——毫无疑问,人总是在变得『更好』——这正是欧洲的劫难——在我们停止惧怕人的同时,我们也失去了对他的热爱、尊敬、期望,失去了对人的追求,看到人就会感到格外厌倦——这不是虚无主义又是什么?我们对人感到厌倦了……

十三 软弱与自欺

言归正传,关于『好人』观念的另外一个起源,也就是仇恨者想像出来的那种好人,这个问题出需要有一个解。羊羔怨恨猛兽毫不奇怪,只是不能因为猛兽捕食羊羔而责怪猛兽。如果羊羔们私下里议论说:『这些猛兽如此之恶,难道和猛兽截然不同,甚至相反的羊羔不能算是好的吗?』那么这样的一种理想的建立并没有什么可以指摘的,尽管猛兽会投过讥讽的一瞥,它们也许会自言自语地说,『我们并不怨恨这些好羊羔,事实上我们很爱它们,没有什么东西比嫩羊羔的味道更好了。』要求强者不表现为强者,要求他不表现征服欲、战胜欲、统治欲,要求他不树敌,不寻找对抗,不渴望凯旋,这就像要求弱者表现为强者一样荒唐。一定量的力相当于同等量的欲念、意志、作为,更确切些说,力不是别的,正是这种欲念、意志、作为本身,只有在语言的迷惑下(理性语言对事物的表述是僵死的,是彻底的谬误),这种力才会显示为其它,因为语言把所有的作为都理解和错解为受制于一个作为着的『主体』。正像常人把闪电和闪电的光分开,把后者看成一个主体的行动、作为并且称其为闪电一样,常人的道德也把强力和它的表现形式分离开来,似乎在强者的背后还有一个中立的基础,强力的表现与否和这个中立的基础毫无关系。可事实上并没有这样的基础;在作为、行动、过程背后并没有一个『存在』;『行动者』只是被想像附加给行动的——行动就是一切。常人让闪电发光,那实际上等于给行动加倍,使之变成行动——行动:也就是把同样一件事一会儿称为原因,一会儿又称为结果。自然科学家也不强似常人,他们说,『力在运动中,力是始因。』我们的全部科学,虽然是极为冷静的,排除了情绪干扰的,但是却仍然受着语言的迷惑,而且始终没能摆脱那些强加上去的替换外壳,即所谓『主体』。

例如,原子就是这样一个替换外壳,同样,康德的『物自体』也是这样一个替换外壳:毫不奇怪,那些被压抑的、在暗中闪耀的报复和仇恨的情感利用了这样一种信念,甚至是空前热烈地信奉这样的信念:即强者可以自由地选择成为弱者,猛兽可以自由地选择变成羔羊。这样一来,他们就为自己赢得了把成为猛兽的归类为猛兽的权利……与此同时,那些被压迫者、被蹂躏者、被战胜者,他们出于无能者渴求复仇的狡猾在窃窃私语:『我们要和那些恶人有所区别,让我们做好人!所有不去侵占、不伤害任何人,不进攻,不求报的人,所有把报复权上交给上帝的人,所有像我们这样隐蔽自己、避开一切罪恶,甚至很少有求于生活的人,像我们这样忍耐、谦恭、正义的人都是好人。』如果冷静而不带偏见地倾听,这段话的真实含义其实不过是:『我们这些弱者的确弱;但是只要我们不去做我们不能胜任的事,这就是好。』但是这种就连昆虫都具有的最低等的智力(昂虫在危险时刻也会佯死,以免行动『过多』),这个冷酷的现实却由于无能的伪造和自欺而被包裹在退缩、平静、等待的道德外衣中,就好像弱者的弱原是他的本质,他的作为,他的全部的、唯一的、必然的、不可替代的真实存在,是一种自发的举动,是某种自愿的选择,是一种行动,一种功绩。这类人相信,一个中立的、随意选择的『主体』必然产生于一种自我保护、自我肯定的本能,这种本能惯于把所有的慌言都神圣化。上述主体,或者说得通俗一点,就是灵魂,或许是迄今为止地球上最好的信仰了,因为它使绝大多数会死亡的人,使各种各样的弱者和受压抑者能够进行高超的自我欺骗,使他们能够把软弱解释为自由,把软弱的这种或那种表现解释为功绩。

十四 理想的制造与虚伪的真相

有谁想上下求索一番、看看理想是怎么制造出来的?谁有这份胆量?……好,让我们开始吧!这儿有一条缝,可以经常窥见这些阴暗的作坊。请稍候片刻,我的冒失大胆先生,您的眼睛必须先习惯于这变幻无常的光线,……好了,现在请告诉我,那里发生了些什么事?说出来您都看到了些什么,您这个最危险的好奇家伙——现在我是倾听者——

——『我什么也没看见,但是我听到的却更多。在那儿从每个角落里都发出一种审慎、狡猾、轻微的耳语。我觉得他们在说慌,每个声响都像沾了蜜糖般的柔软,他们说无疑软弱应当被当作功绩来称赞——您说对了,他们正是这样。』——

——还有什么?

——『不报复的无能应被称为「善良」,卑贱的怯懦应改为「谦卑」,向仇恨的对象屈服应改为「顺从」(根据他们对一个人顺从,这个人吩咐他们屈服,他们称这个人为上帝)。弱者的无害,他特有的怯懦,他倚门而立的态度,他无可奈何的等待,在这儿都被冠上好的名称,被称为「忍耐」,甚至还意味着美德;无能报复被称为不愿报复,甚至还可能称为宽恕(『因为他们不知道他们干的是什么,只有我们才知道他们干的是什么!』)。他们还在议论「爱自己的敌人」——而且边说边淌汗。』

——接着说!

——『我敢断定他们非常悲惨,所有这些耳语者和躲在角落里的伪造者,虽然他们挤做一团取暖。可是他们告诉我说,他们的悲惨是被上帝选中的标志,就像人们鞭打自己最宠爱的狗一样;或许这种悲惨还是一种准备、一种考验、一种训练;或许它竟是以黄金作为巨额利息最终获得补偿的东西,不,不是用黄金,而是用幸福补偿。他们把这种幸福称之为「极乐」』。

——说下去!

——『现在他们向我解释说,尽管他们必须去舔强者和主人的唾沫(不是出于恐惧,绝对不是!而是因为上帝吩咐他们尊敬所有的上级),但他们不仅比这个地球上的那些强者、主人更好,而且他们的「境况也会更好」,至以有朝一日会更好。可是,够了!够了!空气污浊!空气污浊!我觉得这些制造理想的作坊散发着一股弥天大谎的气味。』

——『不,请稍等一下!您还没讲到这些黑色艺术家的绝招呢!他们能把任何一种黑色的物体造成白色的、牛奶般的、纯洁的东西。您难道没有注意到他们魔术的高超?难道没有注意到他们那最大胆、最细致、最聪明、最有欺骗性的手腕?请注意一下!这些满怀报复和仇恨心理的寄生虫,他们从报复和仇恨中究竟造出了些什么?您到底有没有听到那些词句?如果只听他们的言谈,您是否会知道,这些人纯属忌恨者?』

——『我懂了,我再把耳朵竖起来(对!对!对!把呼吸也屏住)。现在我才听到他们已经一再重复过的话:「我们这些好人——我们是正义者。」他们把他们所追求的东西不叫做报复,而称之为「正义的凯旋」;他们仇恨的并不是他们的敌人,不是!他们仇恨「非正义」,仇恨「无视上帝」;他们信仰和期望的不是复仇,不是陶醉于甜蜜的复仇(荷马曾经说过,这种陶醉比蜜糖还甜),而是「上帝的胜利」,是正义的上帝战胜不信上帝的人;这个地球上还值得他们爱的不是那些满怀仇恨的弟兄们,而是他们称之为「充满爱心的弟兄们」,也就是他们所说的地球上所有的好人和正义的人。』

——他们把那种在悲惨生活中给了他们安慰的、关于所谓的未来极乐世界的幻觉叫做什么?

——『什么?我听得准确吗?他们把它叫做「终审日」,他们的王国,即「上帝的王国」到来之日——在这一天到来之前,他们暂且生活在「信仰」、「爱」和「期望」之中。』

——够了!够了!

十五 信仰、爱与期望背后的仇恨与欺骗

信仰什么?爱什么?期望什么?无疑,这些软弱者也希望有朝一日他们能成为强者,有朝一日他们的『王国』也能来临,他们就把这个王国称这『上帝的王国』——他们事事处处都如此谦卑!可是为了获得在这个王国生活的经历,人必须活很长时间的、必须越过死亡,是的,必须获得永生才能够永久地在『上帝的王国』里使自己那『在信仰、爱、期望中』渡过的尘世生活得到补偿。可是补偿什么?用什么来补偿?……我觉得但丁在这里犯了一个大错误,他凭着一种能唤起恐惧感的机灵在通往他的地狱的大门上写下了『我也是被永恒的爱创造的』,——不管怎么说,在通往基督教的天堂和『永恒的极乐』的大门上应当更有理由写上『我也是被永恒的仇恨创造的』,让真理站在通往谎言的大门上!那个天堂的极乐又是什么呢?……我们大概可以猜出答案来了,但是最好还是请一位在这类事情上享誉很高的权威;托马斯·阿奎那,伟大的教师和圣人,来为我们证实一下吧,他用羊羔般温柔的口吻说道:『享福总比受罚能给人以更大的快乐。同样,在天国里,人们会因为亲眼看见恶人受罚而感到快乐。』如果读者愿意听,这儿有一位成功的神父用更强烈的语气表述了同样的思想,他试图劝阻他的基督徒们不要公开地为所欲为——为什么?他非常激烈地写道:『上帝的拯救将给我们以一种完全不同的欢乐,我们拥有的不是身强力壮的人而是殉道者,如果我们想要血,我们就有基督的血……但是想想看,在他凯旋归来之日等待我们的是什么吧!』接下去他继续描绘那迷人的幻景:『是的,还有奇迹会发生——在那最后的永恒的终审日。异教徒从来就不相信会有那一天到来,他们讥讽地说,这整个旧世界连同它的历代居民就将毁于一场大火的那一天决不会到来。可是那一日的奇迹将会是多么宏大,多么广阔!那种景象将会使我惊讶,我将会怎样地大笑,欢乐,狂喜啊!我将会看到那些国王们,那些据称是伟大的国王们,和丘比特一道,和那些在黑暗的深渊中呻吟着的、接到升天通知的人们一道在天堂受到欢迎!我还将看到那些亵渎了耶稣的名字的地方行政官们在火焰中熔化,那火焰比他们出于对基督徒的仇恨而点燃的火焰还要炽热。我还将看到那些先知、那些哲学家们,他们曾教导他们的学生说上帝对任何事都不关心,人并没有灵魂,如果有,那些灵魂也决不会回到他们原来的躯体中。面对着聚在一起的学生们,那些哲学家将会羞愧脸红!此外我还将看到诗人们在审判员席前颤抖,这不是拉达曼陀斯的坐席,不是米诺斯的坐席,而是基督的坐席,是他们从未抬眼看过的基督!而后我还将听到悲剧演员的声音,在他们自己的悲剧中他们的声音更加动人;还有表演家,他们的肢体在火中格外地轻柔。我还会看到四轮马车夫被火轮烧得通红!接下去可以看见体育运动员,他们不是在他们的运动场上,而是被推进火堆——除非我到那时也不想看这一场景,可是依着我的愿望我却要看个够,因为他们曾经把愤怒和怨恨出在上帝的身上;我会说:「这就是他干的,那个木匠或者妓女的儿子(特图里安在这里模仿犹太人的谩骂,我们马上就可以看到,他在犹太法典中用的称呼是耶稣的母亲),那个不遵守安息日的人,那个有魔鬼帮助的撒马利亚人。他就是犹大出卖给你们的那个人,挨了一顿芦杆和拳头,污了一身唾沫,被迫喝了胆汁和醋的那个人。他就是那个被信徒们秘密偷走的人,所以人们说他已经升天了,除非是园丁把他挪走了,以免来访的人群践踏他的菜地!」这是何等样的景象!何等样的狂喜!哪个罗马执政官、会计官、教士能给予你这样的赠礼?可是所有这一切却属于我们,对于精神想像力的信仰勾画了这副图景。但是那些耳闻不见,目睹不到、心感不觉的事物究竟是些什么?我相信,这是比在马戏场、剧院、圆形剧场,或者任何体育场里所能感受到的更大的快乐。』——原文如此。

十六 罗马与犹太的价值观冲突及其现代影响

让我们来总结一下。『好与坏』和『善与恶』这两种对立的价值观在这个地球上进行了一场旷日持久的恶战,虽然第二种价值观长期以来一直稳占上风,但是只要战争仍在持续,胜负的问题就悬而未决;甚至可以说,在此期间战争又升级了,因而它也就变得更深刻,更具有斗智的性质了,结果是目前也许还找不到更确切的标志来标记那超越这种对立的『更高级的自然力』,即更智慧的自然力,那种对立的另一真实的战场。这场战斗的象征在所有人类历史上垂训千古,这就是『罗马人对以色列人,以色列人对罗马人』。迄今为止,还没有比这更重大的战斗,更严峻的课题、更仇视的对立,罗马人把以色列人看成某种违反自然的反常怪物;罗马人认为犹太人『对整个人类充满了仇恨』。如果人们有权把人类的得救和未来同贵族的价值观,即罗马的价值观的无条件统治联系起来,那么罗马人的这种看法就是对的。可是反过来犹太人又是怎样看待罗马人的呢?有千百种迹象表明他们的观念,而我们只需再读一遍圣约翰的《启示录》,那文字史上最偏执狂热的发泄、那对良知的报复。请不要低估基督徒坚韧不拔的本能,他以此为这本仇恨之书贴上了爱的信徒的名字,附加了他狂热地偏爱的那些福音信条——但是不管有多少文字上的诈骗,这里面潜藏着一个事实:罗马人曾经是强壮的、高贵的民族,世界上还没有哪个民族能像罗马人那样,甚至梦想像罗马人那样强壮和高贵;罗马人的所有遗迹、每一个刻痕都是迷人的、庄重的,只要人们能够猜出其中的意思。反之,犹太人却是杰出的、充满怨恨的教士民族,他们具有一种不可比拟的民俗道德天才,我们只需拿中国人和德国人这些有相似天赋的民族和犹太人相比,就可以感受到谁是第一流的天才,谁是第五流的,目前他们之中谁取胜了,是罗马人还是犹太人?可是这里还有什么疑问?想想看,在罗马本土人们把谁当作至高无上的价值的化身,向之鞠躬礼拜——而且不仅在罗马,在差不多整整半个地球上,哪儿的人们变得驯服了,或者将要变得驯服了,那儿的人们就向三个犹太男人和一个犹太女人鞠躬(向拿撒勒斯的耶稣,向渔夫彼得,向地毯匠保罗,向玛丽亚,那个起初被称为耶稣的人的母亲)。这真是奇怪,罗马无疑是战败了。的确,在文艺复兴时期,古典的理想、高贵的价值观念曾经历了光辉夺目的复苏。罗马就像一个假死苏醒的人一样在那座新建的犹太式罗马城的重压下面蠢动起来,那新罗马俨然是一座世界性的犹太教堂,它被称为『教会』。但是,很快地犹太教又一次获胜,这要归功于发生在德国和英国的运动,它被称为宗教改革,而实质上是平民的怨恨运动。伴随这场运动而来的是:教会的重振和古罗马再次被置于古老的墓穴安宁之中。法国革命使犹太教再次取得了对古典理想的更具决定意义的、更深刻的胜利,因为从此,欧洲最后的政治高贵,那盛行于十七——十八世纪的法国精神,在民众怨恨本能的压力下崩溃了,地球上还从未听见过这样热烈的喝彩,这样喧嚣的欢呼!可是在这一过程中出现了一个极为惊人的、根本无法预料的现象:古典理想本身现形了,在人类的眼前和意识中再一次展现出前所未有的光辉;它比以往更强大、更简单、更显著,它大声疾呼反对怨恨者古老的谎言口号:『多数人享有特权』,它反对底层意志、降尊意志、平均意志和使人倒行退化的意志;它喊出可怕的担是令人振奋的反对口号:『少数人享有特权!』拿破仑的出现就像最后一个路标才指示出另外的出路一样。拿破仑,这个最孤独的人,这个跚跚来迟的人,他具体地体现了高贵理想自身的问题——或许我们应当思考,问题究竟何在:拿破仑这个非人和超人的综合体……

十七 善恶的彼岸

到此为止了吗?那些重大的理想对抗就这样被永久地搁置起来了吗?还是只不过推迟了,长时间的推迟了?……是否有朝一日那古老的、憋闷己久的火势必会复燃成可怕得多的烈焰?不仅如此,这难道不正是有人全心全力渴望的吗?甚至有人要求,以至努力促使这一天的到来。如果此时此刻有谁像我的读者一样刚刚开始思考,开始拓展思维,他还很难迅速地得出结论,而我则有足够的理由做出结论,因为还是在很早以前我就很清楚我想要什么,我提出那句危险的口号是为了什么,那句口号写在我上一本书的扉页上:『善恶的彼岸』,至少我没有写上『好坏的彼岸』。

哲学、语言学、生理学与医学的联合探讨

我想利用这篇论文为我提供的时机,公开并正式地表达一个愿望,到目前为止我只是偶尔地同学者们提到过这个愿望,这就是:如果哪个哲学系想要通过提供一系列的学术奖金来促进道德史的研究,那么我目前的这本书也许会对这项计划起有力的推动作用。鉴于这种可能性我想提出下列问题,以供参考。这些问题不论是对于语言学家、历史学家、还是对于以哲学为职业的学者来说都是非常值得关注的:

『语言科学,特别是对语源学的研究,给道德观念的历史发展带来的什么样的启示?』——此外,显然还有必要争取生理学家和医学家来帮助解决这一问题(即迄今为止的价值判断的价值这个问题)。在这里,也仅仅是在这种情况下,应当委托专业哲学家来充当代言人和协调人,因为他们成功地把哲学、生理学和医学之间的那种本来是非常冷淡、非常多疑的关系变成了友好的,富有成果的交往。事实上,所有那些历史研究和人种学研究所熟知的品行戒律,所有那些『你应当……』条款,都要求首先进行生理的阐释和说明,然后才能进行心理的分析,所有类似的问题都要首先经过医学知识的评判。问题的症结在于:各种品行戒律或『道德』价值到底是什么?如果不从各种不同的角度去观察它们,就无法精细地分解『价值目标』。比如某种东西对于某一种生物的长久生存来说可能有明显的价值(对于这种生物提高适应特定气候的能力,或对于它维持最多的数量来说),但是对于造就一种更强壮的生物来说,它就不会具有同样的价值了。大多数的利益和极少数的利益是相互对立的价值观点,认定前者是更高的价值,这属于英国生理学家的天真……现在所有的科学都在为哲学家未来的使命进行准备工作,而哲学家的使命就是:他们必须解决价值的难题,必须确定各种价值的档次。

第二章 『负罪』、『良心谴责』及其它

一 健忘与意志

豢养一种动物,允许它承诺,这岂不正是大自然在人的问题上的两难处境吗?这不正是关于人的真正难题所在吗?至于这个难题已经在很大程度上获得了解决,这在那些善于充分估价健忘的反作用力的人看来,想必是更让人吃惊的事。健忘并不像人们通常所想像的那样,仅仅是一种惯性,它其实是一种活跃的,从最严格的意义上讲是积极主动的障碍力。由于这种障碍力的存在,那些只是为我们所经历、所知晓、所接受的东西在其被消化的过程中(亦可称之为『摄入灵魂』的过程),很少可能进入意识,就像我们用肉体吸收营养(即所谓的『摄入肉体』)的那一整套千篇一律的过程一样。意识的门窗暂时地关闭起来了,以免受到那些本来应由我们的低级服务器官对付的噪音和争斗的骚扰,从而使意识能够获得片刻的宁静、些许的空白,使意识还能够有地方留给新的东西,特别是留给更为高尚的工作和工作人员,留给支配、预测和规划(因为我们机体的结构是寡头式的)——这就是我们恰才说到的积极健忘的功用,它像个门房,像个灵魂秩序的保姆,像个安宁和规矩的保姆,显而易见,假如没有健忘,那么幸福、快乐、期望、骄傲、现实存在,所有这些在很大程度上也不复存在。如果有一个人,他的这一障碍机关受损或失灵,那么这个人就像(而且不只是像……)一个消化不良的人。他将什么也不能够『成就』。恰恰是在这个必须要健忘的动物身上,遗忘表现为一种力量,一种体魄强健的形式。这个动物为自己培养了一种反作用力,一种记忆,他借助这种力量在特定的情况下——在事关承诺的情况下,公开地表现出健忘。因此,他绝不仅仅是被动地无法摆脱已建立的印象,不是无法消除曾经许下的、无法实现的诺言,而是积极主动地不欲摆脱已建立的印象,是持续不断地渴求曾经一度渴求的东西,是名符其实的意志记忆。所以在最初的『我要』、『我将要做』和意志的真实发泄、意志的行为之间无疑可以夹进一个充满新鲜事物、陌生环境、甚至意志行为的世界,而无需扯断意志的长链。但这一切的前提条件是什么?为了能够支配未来,人就得事先学会区别必然和偶然,学会思考因果,学会观察现状和远景,并且弄清什么是目的,什么是达到这一目的所需要的手段,学会准确地预测,甚至估计、估算——为了能够像许诺者一样最终实现关于自己的未来的预言,人本身就得先变得可估算、有规律,有必然性!

二 责任的起源

这就是责任的起源的漫长历史。我们已经看到,那项培养一种可以许诺的动物的任务包含了较近期的、作为先决条件和准备工作的任务,即先在一定程度上把人变成必然的、单调的、平等的、有规律的,因而也是可估算的。我称之为『道德习俗』①的非凡劳动,人在人类自身发展的漫长历程中所从事的真正的劳动,人的全部史前劳动都因而有了意义,得到了正名,不管这些劳动中包含了多少冷酷、残暴、愚蠢、荒谬,但是借助于道德习俗和社会紧箍咒的力量,人确实会被变得可以估算。如果我们站在这一非凡过程的终点,处于树木终于结出果实,社团及其道德习俗终于暴露了目的的时候,我们就会发现,这棵树木最成熟的果实是自主的个体,这个个体只对他自己来说是平等的,他又一次摆脱了一切道德习俗的约束,成了自治的、超道德习俗的个体(因为『自治』和『道德习俗』相悖);总而言之,我们发现的是一个具有自己独立的长期意志的人,一个可以许诺的人,他有一种骄傲的、在每一条肌肉中震颠着的意识,他终于赢得了这意识、这生动活泼的意识,这关于力量和自由的真实意识,总之,这是一种人的成就感。这个获得了自由的人,这个真的能够许诺的人,这个自由意志的主人,这个行使主权的人,他怎能不意识到自己比所有那些不能许诺,不能为自己辩护的人都要优越?试想,他激发了多少信任?多少恐惧?多少尊敬?——他『理应』被人信任、惧怕和尊敬。再试想,这个能够统治自己的人,他怎能不势所必然地也去统治周围的环境、自然,以及所有意志薄弱、不可信任的人?『自由』人,具有长久不懈的意志的人,也有他的价值标准:他从自己的角度出发去尊敬或蔑视别人,他必然会尊敬和他同等的、强壮的、可信赖的人(即可以许诺的人),也就是说任何一个能够像自主的人那样对诺言抱审慎持重态度的人;他不轻信,他的信任就标志着杰出;他的话是算数可信的,因为他知道他自己有足够的力量应付不测,甚至『抵抗命运』;同样,他也必然要随时准备用脚踢那些随意许诺的削肩的轻浮鬼,随时准备鞭打那些说话不算数的骗子。他骄傲地意识到,负责任是非同寻常的特权,是少有的自由,是驾驭自己的权力。这种意识已经深入到他的心底,变成了他的本能,一种支配性的本能。他会把这种本能叫做什么呢?他是否有必要为它找个名称?当然,这个独立自主的人肯定地会把这种本能称之为他的良心……

①参见《曙光》第七,十三,十六页。

三 记忆与责任

他的良心?……显然,『良心』这个概念(我们现在看到的是它的最高的,近乎惊人的形式)已经经历了一个漫长的历史和形式转换过程。如前所述,能够为自己称道,能够骄傲地肯定自己——这是一种成熟的果实,但也是近期的果实——这果实要酸涩地在树上挂悬多久啊!可是还有更长的时间根本看不到这种果实的影子!——没有人能够许诺它的出现,尽管树木已经具备了一切适应这种果实生长的条件!『人这种动物的记忆是怎么出现的?这半是愚钝、半是轻率的片刻理解力,这积极主动的健忘到底是怎么被打上记忆的烙印,一直保留到今天的?……』可以想见,这个古老的难题无法只靠温文尔雅的回答和手段得到解决;也许在人的整个史前时期根本不存在比人的记忆术更为阴森可怖的东西了。『人烙刻了某种东西,使之停留在记忆里:只有不断引起疼痛的东西才不会被忘记。』——这是人类心理学的一个最古老(可惜也是最持久)的原理。有人还想说,在这个世上,只要哪里还有庄重、严厉、机密,只要哪里的人和民众还生活在暗淡的阴影中,曾经一度被普遍地许诺、担保、赞誉的那种恐怖的残余就会继续起作用:过去,那最漫长、最深沉、最严酷的过去,每当我们变得『严厉』起来的时候,它就会对我们大喝一声,从我们心底喷涌而出;每当人们认为有必要留下记忆的时候,就会发生流血、酷刑和牺牲;那最恐怖的牺牲和祭品(诸如牺牲头生子),那最可怕的截肢(例如阉割),那些所有宗教礼仪中最残酷的仪式(所有的宗教归根结底都是残酷的体系),——所有这一切都起源于那个本能,它揭示了疼痛是维持记忆力的最强有力的手段。从某种意义上讲,这里还应当算上全部禁欲主义行为:有些思想需要延续不断,无所不在,难以忘却,需要被『固定』下来,通过这些『固定思想』,以及禁欲程序和生活方式,给整个神经和思想系统催眠,目的是为了把这些思想从和其它思想的竞争中解脱出来,使其变成『难以忘却』的。人类的『记忆力』越差,他们的习俗就越是可怕。严酷的惩罚条例特别为我们提供了一个标准,可以用来衡量他们花费了多少努力以克服健忘,并且在现代为眼下这些情感和欲念的奴隶们保留一些适用于社会共同生活的原始要求。我们这些德国人当然不会把我们自己看成是一个特别残酷和铁石心肠的民族,更不会看成是一个特别放荡不羁和得过且过的民族;可是只要看看我们古老的惩罚条例就不难发现,造就一个『思想家的民族』需要进行何等的努力(我们要说,在欧洲人民中至今还可以找到最多的信任、严厉、乏味和求实精神,这些特性使得我们能够培养出各式各样的欧洲官人)。为了控制他们的暴民本能和野蛮粗俗,这些德国人用了可怖的方法维持记忆。想想古老的德国刑罚,比如石刑(据说是用石磨盘砸罪人的头)、车磔(这是惩罚术王国中德国天才的原始发明和专长!)、钉木刺、『四马分尸』、油煎或酒煮(十四世纪和十五世纪还在用此刑)、广泛使用的剥皮(『刀切皮』)、胸前割肉,还有给罪犯涂上蜂蜜,放在太阳下曝晒,让蚊蝇叮咬。借助着这些刑罚人们终于记住了五、六个『我不要』,人们就此许下诺言,以便能够享受社团生活的好处——确实!借助于这种记忆,人们终于达到了『理性』!——啊!理性,严厉,控制感情,所有这些意味着深思熟虑的暗淡的东西,所有这些人类的特权和珍品,它们的代价有多高啊!在这些『好东西』背后有多少血和恐怖啊!

四 负罪的起源

可是另外那种『暗淡的东西』,那种对于负罪的意识,那一整套『良心谴责』,又都是怎么问世的呢?还是回到我们的道德谱系家们这儿来吧。让我再重复一遍(也许我还未曾提到过),他们毫无用处;他们只有自己那五柞长的、纯粹是『现代化』的经历;他们不了解过,也没有愿望了解过去;特别是他们缺乏一种历史本能,一种在这儿恰恰是必要的『第二预感能力』;——然而他们竟要写作道德的历史:这种尝试势必以产生和事实不符的结果而告终。以往的这些道德谱系家们恐伯连在梦里都未曾想到过,『负罪』这个主要的道德概念来源于『欠债』这个非常物质化的概念;惩罚作为一种回报,它的发展和有关意志自由的任何命题都毫无关系。当然,历史总是需要首先发展到了人性的高级阶段,『人』这种动物才开始把那些非常原始的罪行区分为『故意的』、『疏忽的』、『意外的』、『应负刑事责任的』,并且开始在对立的立场上进行量刑。那个现在变得如此般廉价,显得如此般自然、如此般必要的观念,那个解释了公正感的由来的观念,那个被迫承认『罪犯应当受到惩罚,因为他本来有其它的选择余地』的观念,它的的确确地很晚才出现的,是人的精练的辨别形式和决断形式;如果有谁把它挪到人类发展之初,他就是粗暴地曲解了古人类的心理。在整个人类历史的一段极为漫长的时期里是不存在着刑罚的,因为人们能够使肇事者对自己的行为负责。当时奉行的原则也并不只是惩罚有罪的人,而是像今天的父母惩罚他们的孩子那样,出于对肇事者造成的损失的气忿——但是这种气忿是有限度的,也是可以缓和的,因为人们会想到任何损失都可以找到相应的补偿,甚至使肇事者感到疼痛也可以做为一种补偿。这种古老的、根深蒂固的、也许现在已无法根除的观念,这种用疼痛抵偿损失的观念是怎么产生的?我已经猜到了:它产生于债权人和债务人之间的契约关系中。这种契约关系和『权利主体』的观念一样古老,而后者还涉及到买卖、交换、贸易、交通的基本形成。

五 契约、惩罚与权力